Spirits of French Lick

Walk into French Lick Winery, located in the old Kimball piano factory in West Baden, and it’s all glass bottle beauty lining the walls of the gift shop next to The Vintage Café. You won’t find any ivories to tickle now, though you will meet Coco, the caricature of a French woman who serves as the winery’s unofficial mascot, featured on the labels of their sweet fruit wines distributed throughout the country. Bunches of purple grapes mark the labels of estate-bottled wines, made from 10 different varietals grown on the winery’s own Hoosier Homestead– designated farm in nearby Martin County.

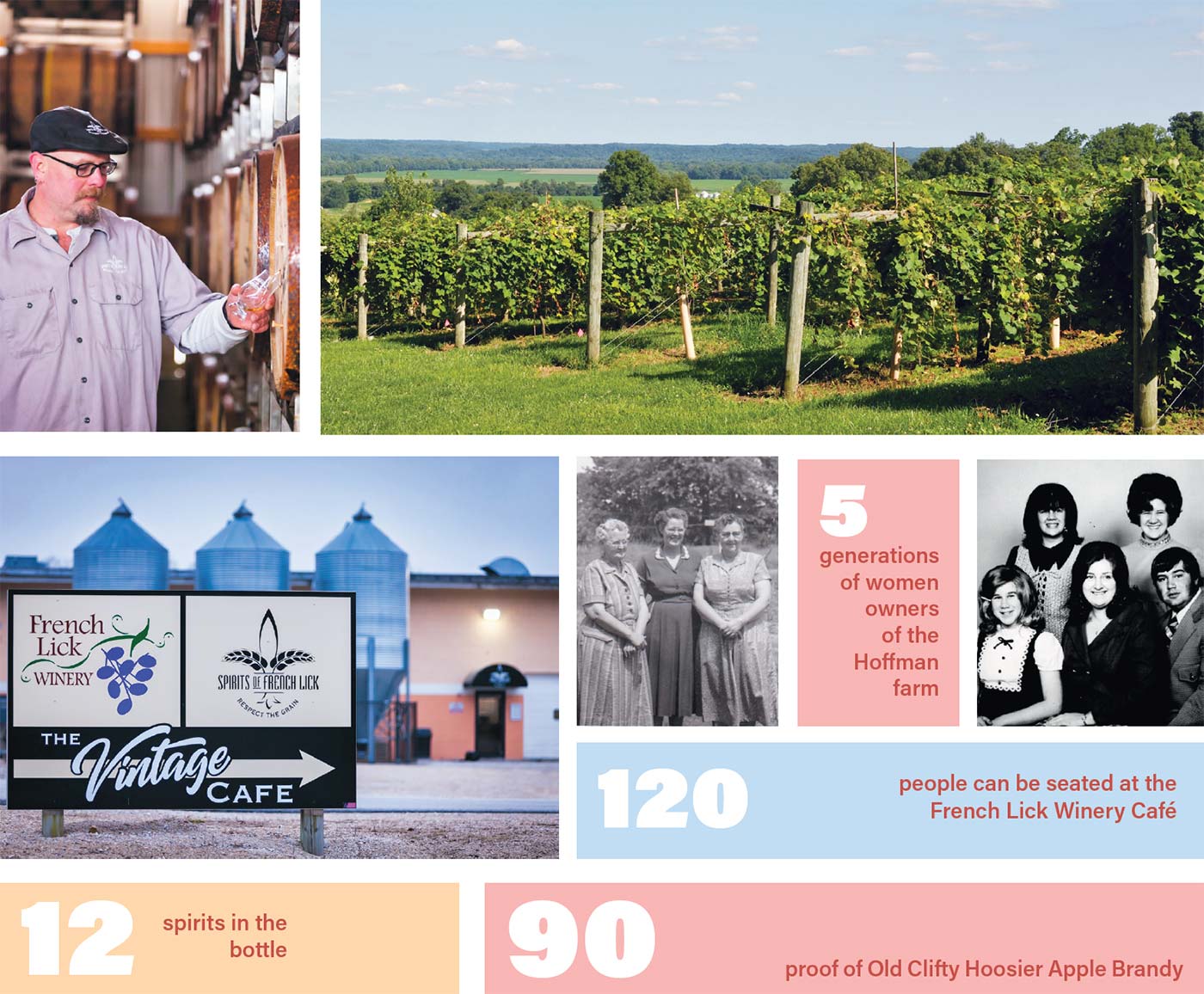

Look closer and you’ll also find several other shelves filled with house-made brandy and bourbon, gin and rum, absinthe, aquavit and vodka. These are the spirits produced by the winery’s sister distillery, Spirits of French Lick. But once you’ve stayed a while, and especially after you’ve toured the place, you’ll meet the real spirits behind this family-owned operation that goes back much further than the 25 years they’ve been in business.

INDIANA'S BLACK FOREST

To get the full story, you have to go back more than a century, to the mid-1800s, when a six-county region of southern Indiana—Orange, Washington, Crawford, Harrison, Lawrence, and Perry counties—was known as the Black Forest of Indiana. As part of the fruit belt of the United States, this area, which stretches from Bedford and Salem down to Tell City and Corydon, boasted nearly a million apple trees.

But that didn’t mean southern Indiana became known for its fruit pies and pastries. In fact, as Michael Pollan writes in The Botany of Desire, “Up until Prohibition, an apple grown in America was far less likely to be eaten than to wind up in a barrel of cider.” The same was true in Indiana’s Black Forest: German immigrants brought Old-Country techniques and tastes with them, producing more apple brandy than any other area of the world. From 1855 to 1914, more than 150 legal distilleries were producing brandy and other spirits in the area, with hundreds more personal stills tucked into barns and sheds throughout the hilly region.

A THREATENED INDUSTRY

But the distilling industry faced constant threats just after the turn of the century: from federal agents looking for tax dollars to a fungus known as fire blight to the rapidly growing temperance movement. When Prohibition became federal law from 1920 to 1933, it not only took down the legal spirits business but also thousands of acres of fruit trees, cut down and burned by federal Prohibition officers and state excise police during raids on bootleggers.

When Prohibition ended, a few Indiana distilleries reopened, but the production of brandy, bourbon, and other spirits had changed dramatically, constrained by federal laws that prohibited distilling without a license and state laws that forced distillers to sell only through wholesale distribution.

A FARMING LEGACY

Meanwhile, during the heyday of Hoosier distilling, another family immigrated from Bavaria, Germany, through New Orleans, ultimately settling just west of Indiana’s Black Forest in Martin County. George Hoffman, the great-great-grandfather of Kim Doty—who along with her husband, sons and daughter-in-law owns French Lick Winery and the Spirits of French Lick—purchased a 515-acre farm along the east fork of the White River. Hoffman and his wife, Barbara, built a house and began farming the tillable acres. The couple’s only son, Christian, passed away as a teenager, so when George and Barbara passed away years later, the farm was divided between their two daughters, Sophia and Mattie.

Sophia, Kim’s great-grandmother, passed her half of the farm down to her daughter Eathel (Sophia’s other daughter, Viola, died at a young age). Then, in 1958, Barbara Sue (aka Susie) Klingle, Eathel’s daughter and Kim’s mother, bought her mom’s half of the farm plus her greataunt Mattie’s half, effectively restoring the original Hoffman farm.

Pictured upper right: Distiller, Alan Bishop; upper left: photograph: French Lick winery; middle left: photograph: Hoffman Family

A VINEYARD ON THE TOP 40

In the mid 1990s, the next generation set their sights on the Hoffman farm. It began when Kim and her husband, John, decided to rent a 40- acre plot of hilly, well-drained land—what they call the “Top 40”—from her mom’s farm to plant a vineyard. It was intended as a side project, since Kim worked full-time as a postmaster for the U.S. Postal Service and John as a vice president of a local bank. But when they spoke with a local vintner about selling future harvests to him, he suggested the Dotys start a winery themselves— the only way to really make money from a vineyard, he told them.

“At the time, there were only 10 wineries in the state; we were the 11th,” Kim says. “We’d always wanted to own our own business. And at the time, we really wanted to grow grapes.”

John had experience with winemaking, having fermented home batches in the family’s basement for years. So in 1995, the Dotys opened French Lick Winery, now part of the Indiana Uplands Wine Trail, in the basement of French Lick’s Beechwood Mansion. They began by fermenting fruit they purchased, using the profits to establish their eight-acre Heaven’s View Vineyard in 1997. They produced the first wine from their own grapes in 1998.

Initially, the vineyard and the winery were all the couple had in mind. After all, they were both still working fulltime and raising a family. But around 2000, things began to change.

FROM VINEYARD TO DISTILLERY

First, the couple purchased the Top 40, along with more than 200 additional acres of her mom’s farm, becoming the fifth generation of female landowners in the family. In 2005, the winery moved into one-third of the vacant Kimball factory and opened The Vintage Café and gift shop. The same year, John retired from the bank; four years later, Kim also took an early retirement from the USPS, allowing the couple to commit full-time to the business’s success. The distillery was the latest addition to the Dotys’ venture, made possible by a 2013 change in Indiana law allowing Hoosiers to operate small, craft distilleries, serve tasting room samples and sell bottles of spirits on premises. In 2016, the Dotys launched Spirits of French Lick, with Alan Bishop, who grew up on a farm in nearby Washington County, as head distiller.

RESPECT THE PAST

For Alan, local lore, traditional methods and ancient wisdom are integral to every aspect of the business: from sourcing ingredients to naming products. While he does take advantage of technology to help him keep precise temperatures in his double-pot distillation process, he mostly does things the old-fashioned way: manually moving the mash from cooker to fermenter, cutting each run by hand and using his senses to smell, taste and even touch his way to the perfect brew. “I don’t want a computer making my whiskey,” Alan says. “We’re doing things people haven’t seen for a hundred years or more.”

RESPECT THE GRAIN

Alan’s commitment to tradition also extends into the yeasts and grains he uses, connecting Spirits of French Lick back to the local history of distilling and farming. For instance, Alan himself harvested dormant yeast strains from three now-defunct distilleries around the region. Whenever possible, the corn and wheat milled, cooked and fermented into spirits are grown on the Dotys’ Hoosier Homestead farm. Other grains are sourced as locally as possible.

Behind that is grain has terroir the same way grapes do,” Alan explains. “So depending on where the grain is grown, the minerals in the soil, the environment that surrounds it and the way that it’s grown—that’s going to have an impact on the flavor.” In other words, the spirits of French Lick literally live on in the distilled spirits.

LOOKING TO THE FUTURE

The spirits also live on through the family farm, now known as the Klingle Doty Farm, as Kim and John plan to pass the baton to their sons, Nick and Aaron, who both are part owners of and work at French Lick Winery. And though this sixth generation may not carry on the tradition of female ownership, Kim is hopeful for the seventh generation. Nick and his wife, Laurelin, have three daughters: Isabel, 7, Gwendolyn, 5, and Piper, 3.

“I’ve been extremely proud to have this ancestry and be tied to this land,” Kim says. “I hope the girls will keep the farm in the family and for the business.”

TRUE SPIRITS OF FRENCH LICK

Several of the spirits produced by Spirits of French Lick are part of the “Classic Line,” named after historical figures, local distilleries, and other cultural icons. Here are a few of our favorites.

Old Clifty Hoosier Apple Brandy is named for The Old Clifty distillery, which was located in what is now the Cave River Valley Nature Preserve north of Campbellsburg Indiana. From 1818 to 1904, the distillery averaged about 20,000 gallons of apple brandy each year.

Lee W. Sinclair 4-Grain Bourbon, a silver award winner at the 2019 North American Bourbon & Whiskey Competition, was named after the Hoosier businessman who purchased the West Baden Springs Hotel in 1888 after seeing its potential as a holiday resort. When a fire destroyed the entire lodging structure in 1901, Sinclair rebuilt the hotel including the grand atrium with its circular dome ceiling.

Maddie Gladden High Rye Bourbon, available in 2020, is named for a local madam who brought her successful Nashville business back to her hometown of Salem, Ind., in the 1890s. According to the Louisville Courier Journal, Gladden “had a fine Victorian mansion constructed right on the main street of town and opened her business to the delight of wealthy businessmen traveling from Chicago to Louisville via the Monon Railroad.”

William Dalton Bottled in Bond Bourbon, available in 2021, named after the master distiller of the old Spring Mill Village distillery. A representation of the distillery was rebuilt in 1932 using logs salvaged from the original site as part of the historical village in Spring Mill State Park.

Fascination Street Barrel Aged Absinthe, available in 2020, is named for one of Alan Bishop’s favorite songs by British rock bank The Cure. Cure vocalist and primary songwriter Robert Smith supposedly wrote “Fascination Street” in anticipation of a visit to Bourbon Street in New Orleans.