REVITALIZING INDIGENOUS CUISINE

A conversation with Sean Sherman, founder of The Sioux Chef

A striking feature of modern-day Europe—an ancestral origin for many of North America’s current inhabitants—rests in the continuing cultural relevance of the ancient. To travel there as an American might leave the faintly sour taste of something lost, some link to history to whose strange absence we routinely turn a blind eye.

Shadowed by the Colosseum or the Pantheon, the stories of Lewis and Clark, Abe Lincoln and Laura Ingalls Wilder seem modern. Popular history prior to the Pilgrims appears to trail off. What history we have of indigenous peoples and the way they lived was mangled by war, genocide, forced migrations and institutionalized racism or otherwise intentionally forgotten.

Yet even rooted in such a dark and distorted past, the vision of the future is bright and clear.

Sean Sherman, a member of the Oglala Lakota subtribe of the Great Sioux Nation and founder of The Sioux Chef, the Indigenous Food Lab and the nonprofit North American Traditional Indigenous Food Systems (NATIFS), is on a mission to revitalize Native American cuisine. In the process, his work is re-identifying North American cuisine, reclaiming an important culinary culture long buried and often inaccessible.

His cooking focuses on indigenous foods (pre-colonization) and the traditional methods of preparing them. Sherman is intent on reconnecting us to the North America before beef, pork, chicken, dairy, flour or refined sugar. He is well on his way to starting an edible revolution and rekindling our relationship to truly American food.

Q: Tell us the moment this all got started.

Sean Sherman: In 2008, I was living down in Mexico, about an hour north of Puerto Vallarta in a little town called San Pancho. I was in between jobs, trying to figure out my next move. One day I was on the beach, and groups of indigenous people, the Huichol, were sitting out, selling their art. The art was so similar to the things I saw growing up Lakota. Seeing so many commonalities, it really just struck me that as a chef I should focus on my own heritage. The problem was, I didn’t know that much about Lakota food.

Suddenly I had so many questions: What were my Lakota ancestors eating? Were they growing food? What kind of foods where they collecting? How are they preserving things? Where did they get salt? What kind of fats did they use? I kept thinking about everything, especially from a chef’s perspective, and breaking it down. I am learning more and more every year. There is so much untapped knowledge when it comes to indigenous food systems all around the world.

“Land cannot be properly cared for by people who do not know it intimately, who do not know how to care for it, who are not strongly motivated to care for it.” — Wendell Berry

Q: What are you working on these days?

A: My partner, Dana Thompson, and I just started our own nonprofit called NATIFS, North American Traditional Indigenous Food Systems. We are opening a restaurant through NATIFS that also has a training and educational center. [All under the brand, the Indigenous Food Lab (IFL).] IFL will be a place where people can come and learn about facets of indigenous food: agriculture, wild foods, cooking and food preservation. The restaurant will become a training center for the tribes around us, to help them develop their own food businesses. Eventually, we want to open up IFLs all over the country.

We are also opening another for-profit restaurant in Minneapolis, right downtown in front of the Mississippi River. We will be able to tell the story of the Lakota people, because the river is a uniquely spiritual place, although obviously all of the natural features are gone because of industrialization.

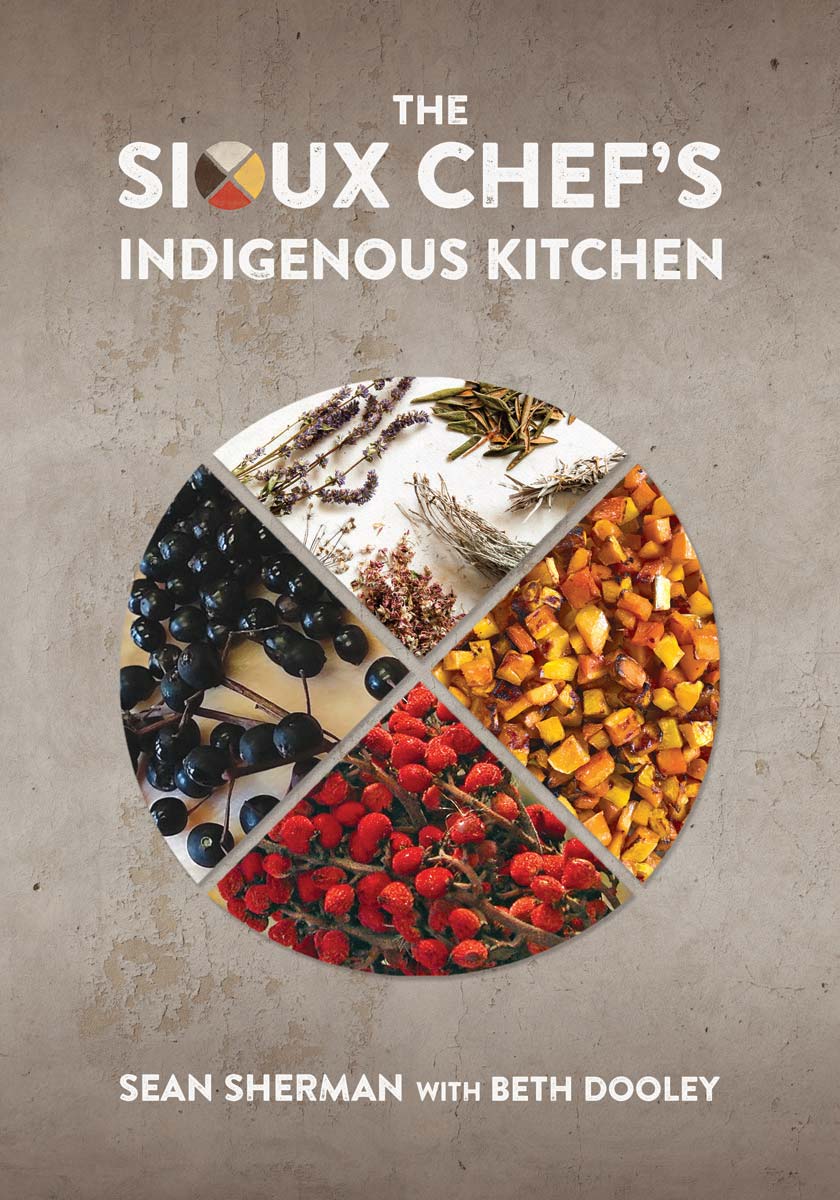

Also, the cookbook [The Sioux Chef’s Indigenous Kitchen] is out, which has kept us really busy. We just did a big East Coast push and we are getting ready to do a West Coast push.

Q: Do you think your projects relate to the American farm-to-table movement or the sustainable food movement?

A: I think it’s just a matter of really good timing that people are beginning to understand the importance of locality in sustainability. However, I think this is a lot deeper than that. I think this is about having the deeper understanding of the landscape that people are standing on, understanding that there was history in the United States before Laura Ingalls [Wilder, author of the Little House on the Prairie books]. There were many cultures, and many people, and so much diversification surrounding food systems. That is why learning indigenous knowledge can help us develop a deeper understanding of the land that we are standing on and grew up on.

Q: What are people’s general reactions to your projects, and to the food itself ?

A: It’s been overwhelmingly positive. We are doing simple foods, but really clean foods. You know it’s such a healthy diet, especially after we removed all dairy, wheat, processed sugar and just showcased alternative proteins and things like that. Plus there is the whole historical aspect of it. I think people find something interesting in the mix of it, whether it’s wild food, native agriculture, native history or just cooking. We do a lot of fancy meals, but we also do a lot of really simple group meals.

Q: Do you think that the work that you are doing will help to revitalize biodiversity?

A: Absolutely. It’s really getting people to embrace the regional diversity that we have right here in North America, and understanding that we have all this unique food—vegetable and animal protein, cooking techniques—all over the place.

There is so much to embrace, and it could really create a better sense of regional North American food everywhere.

Q: So do you hope that this will reach more people than just Native American peoples?

A: There is a pretty diverse crowd that gets it, that North America has to accept and understand its indigenous roots to really grow. We’ve had the opportunity to travel to Europe, work with Noma, the Nordic Food Lab, chefs in France, Slow Food University, Yale, Brown, the Smithsonian, the CIA, James Beard Institute and things like that.

Q: What would you say is your ideal utopian vision for America?

A: I think for a utopian vision it’s really about embracing a lot of that knowledge and applying it to wherever we are. So things like landscaping with a purpose, to produce food and medicine directly around you. Utilizing a lot more natural medicines, too. Because all of these plants have amazing medicinal properties that the indigenous people know very well, and getting away from pharmaceuticals as the answer for everything. Embracing our regional biodiversity, bringing those regions together, and making it easier for all of us to connect with our land no matter where we are. Because if we are going to produce enough food for the future, with the population continuing to climb, we really have to approach how wasteful we are as a society and come up with ways to get resourceful with the stuff that’s around us. There are a lot of lessons within indigenous communities and histories that we can apply for those pieces.

Q: So, if you had to give advice to the average Midwesterner on what they could do to start getting more in touch with the land they stand on, what would you say?

A: (Laughter) “The average”? Well, part of it we really tried to spell out well with the cookbook. To give people a nice overview and some simple recipes that utilize plants that are probably in their backyard. I think that is a good starting place for anyone who is looking to live more sustainably and with a deeper knowledge of their area.

For more information about Chef Sean Sherman, his mission and how to grow your relationship with North American food, check out his James Beard Award– winning cookbook: The Sioux Chef’s Indigenous Kitchen. Available now at bookstores near you, or online at Sioux-Chef.com

Indigenous?

The dictionary defines indigenous as originating or occurring naturally in a place. As far as the ecology of North America is concerned, indigenous refers to the period prior to European “discovery.” Since 12,000–15,000 B.C.E,, long before Columbus ever sailed the ocean blue, human beings have lived and thrived on the continent we now call home.

That means that for 12,000 years, indigenous peoples lived without chicken, pork, beef, dairy, refined sugar, wheat, olive oil, bananas, oranges and apples.

Instead, what indigenous peoples had were remarkably contemporary methods of cultivating and collecting food. They collected native plants like wood sorrel, purslane, plantain and lamb’s quarter–wild superfoods more powerful than kale and so well adapted to the climate that they could grow without fertilizers or pesticides.

They gathered wild nuts like acorns, and processed them into protein-rich flour (both gluten-free and low-glycemic). They hunted wild game like rabbit, turkey, duck and pheasant, and never forgot to use the organ meats containing folic acid, iron, chromium, copper, selenium, omega fatty acids, zinc and an alphabet of vitamins. Indigenous people never needed health guidelines like Paleo, Whole 30 or the “food pyramid”; they simply ate food balanced by the ecosystem. The indigenous diet designed by nature works with nature, and so works to conserve and sustain the land. To quote Wendell Berry, poet, farmer and lifelong Kentuckian, “Land cannot be properly cared for by people who do not know it intimately, who do not know how to care for it, who are not strongly motivated to care for it.”

Maybe the word “indigenous” describes something much wider and deeper than the dictionary could ever explain. Maybe it describes the way we can begin to see ourselves as originating or occurring naturally from a place, the way to value the land we stand on as if it had created us.

Today, as we struggle to understand the chronic health problems and environmental threats looming over us, perhaps exploring the connection that indigenous people once shared with this land and that we, the current inhabitants of North America, share with them may have something to teach us.