TASTE OF THE PAST

Food writer Jonathan Kauffman on being a Hoosier, memories from a “brown-food” childhood and his new book

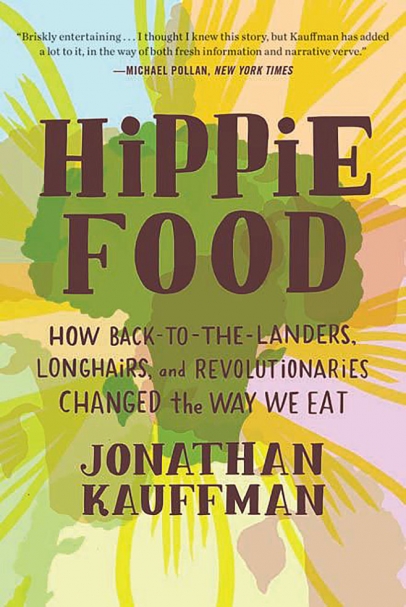

Did you know there is such a thing as “hippie food? Well, Jonathan Kauffman has written a book about this now American tradition in cuisine, and it’s well worth the winter read. Kauffman is “a line cook turned journalist” who grew up in Northern Indiana in a Mennonite family and now lives in San Francisco. An accomplished food writer and devoted cook, he dedicated years of research to telling the story of how foods that are ubiquitous to our local food co-op used to be exotic items from other worlds brought to the U.S. by traveling youth like Alice Waters and Americans who were in search of healthier, simpler options for the dining room table. Tofu, brown rice, yogurt and whole-grain breads were all new, fresh foods during the 1960s and 1970s. Their introduction into the U.S. diet then, Kauffman details, is what has led to a lot of what defines our food culture now. We wanted to talk with this hippie-kid Hoosier who now calls the West Coast his home and to learn more about his book, baking bread with his mom and what hippie food could look like in the future.

Q: As a child of the ’70s, what did your childhood taste like and how did hippie food play a part?

A: When I think of the food I grew up with, the first word that comes to mind is “brown” and the second is “eclectic.” We ate a lot of lentils in the 1970s, and our church potlucks always had a Crock-Pot section for stews. Thanks to Doris Janzen Longacre’s 1976 More-With-Less Cookbook, which asked how Americans could eat more sustainably and found the answer in whole foods and recipes from Asia, Africa and Latin America, Mennonites of my parents’ generation made a greater effort to abandon grocery-store processed foods and expand their palates. Dinner at my house could be African groundnut stew one night, broccoli-and-tofu stir-fry the next. Now that I’m older I realize that my parents were as adventurous as they were earnest in their food choices.

Q: Growing up in Northern Indiana, where did your food come from? Did your parents grow their own food? And what natural food stores or co-ops, if any, were established back then?

A: My parents both grew up in rural parts of the Midwest—Ohio and Northern Michigan—and so it seemed natural to them to return to canning and freezing massive quantities of applesauce, jam, fruit, green beans every summer, and buying beef by the quarter-animal from a local butcher. They gardened with other families in our congregation when I was very young, and maintained a backyard vegetable patch through my early teenage years.

Many of my shopping memories from the 1970s centered around the Elkhart Co-op, which my mother volunteered at. One of my personal goals while researching this book was to find out how Elkhart came to have a food co-op in the 1970s. It closed decades ago, though the nearby Goshen food co-op is still open. While I couldn’t locate any of the founders of the Elkhart store, I was fascinated to discover the Michigan Federation of Food Co-ops, based in Ann Arbor. The federation enabled hundreds of small buying clubs and co-ops around Michigan, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois to flourish, supplying stores like ours with bulk foods and natural foods products. It also linked up with other regional co-op hubs so that organic Michigan beans could be sold in Minnesota and Iowa. (The Midwest played a huge role, both intellectually and organizationally, in the 1970s natural foods movement.) Though the federation didn’t survive the great co-op die-off of the 1990s and the consolidation of the natural-foods industry, the scope of the organization, as well as its dedication to operating collectively, was inspiring.

Q: How has hippie food evolved from the ’70s to the 21st century, and what do you think it will look like in the future?

A: Certain aspects of the 1970s hippie food movement, such as grain bowls and sprouted legumes, have come back into fashion. At the same time, many fringe hippie foods from that time never disappeared. Instead, they went mainstream. People born in the 1980s and the 1990s have no idea that yogurt, granola, whole-wheat bread, organic vegetables and tofu were once strange, suspect substances, pooh-poohed by academic nutritionists as well as the mainstream media.

If we look at today’s health-oriented food, such as smoothies and quinoa, as modern hippie food, it’s more colorful, more flavorful and lighter than 1970s natural foods recipes. (Before the low-fat movement of the 1980s, vegetarian food drowned in cream and cheese.) Because grocery stores carry a much broader range of ingredients, current-day hippie food uses more varied ingredients and is even more internationally influenced than the 1970s. It’s the food I cook at home.

I do think that, because we’ve collectively realized their significance to our health, whole grains, dairy and meat substitutes and organic produce will play an even more central role in our diets. Whatever the hippie food of the future is, it will be incubated on the shelves of natural- foods stores, which are quick to pick up on every new diet. I think that the Paleo, keto and gluten-free diets will fade away—I’m talking about people who pick up those diets for lifestyle reasons, not health concerns—but many of the ingredients that they popularized will be in our pantries 30 years from now.

Q: Winter is the time to bake, and I understand your mom used to bake when you were growing up. What are some of the breads your mom used to make that are in your repertoire and why are they important to your home kitchen?

A: My parents, thank goodness, were never so hardcore about their diets that food was grim—I definitely know a few people my age who are still in recovery from their brown-food childhoods. Mennonites do love their desserts, and my mom was no exception, so I still grew up with pies and cinnamon rolls as well as homemade bread. All through my 30s I baked her oatmeal bread and a wheat-rye-corn bread from More-With- Less every week to toast for breakfast. Right now I start my days with protein smoothies, so I don’t bake as much as I used to, but my mom gave me a great gift in demystifying the act of making bread. Baking has always been a centering act for me rather than a forbidding, alchemical pursuit. There’s no smell more comforting than that of a loaf of bread in the oven.

Find Kauffman’s book Hippie Food: How Back-to-the-Landers, Longhairs, and Revolutionaries Changed the Way We Eat at a local independent bookstore near you.