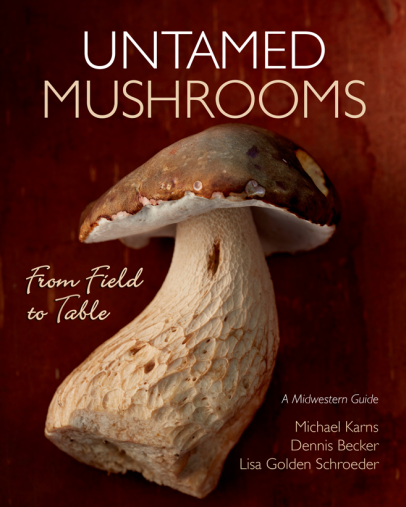

Untamed Mushrooms: From Field to Table

Morels

Yellow Morel (Morchella esculentoides) and Black Morel (Morchella septentrionalis or Morchella angusticeps)

Morel mushrooms are probably the most widely harvested of all varieties of wild mushroom species in the United States. The broad distribution of the different species of this genus and the ease of identification contribute to their popularity. In Minnesota, the morel has been granted status as the “official” state mushroom.

Familiarity is evidenced in the many colloquial names given to morels across the country. From sponge mushrooms to molly moochers and merkels or hickory chickens, morels are a choice edible, one of the first to arrive after a long, cold winter. The spring equinox marks the point when winter is done and mushroom season will shortly be at hand. It’s my alarm clock, so to speak, reminding me that I must prepare for the arrival of those long-awaited fungal friends. There are boots to dress with waterproofing, knives to sharpen, foraging clothes to treat for ticks, and many other odds and ends to tend to before setting out into the fields and forests.

A scant month later, and black morels will begin reaching up from the depths of the obscured and complex world of the soil. Each sunny day warms the earth a bit more, and the melting snow seeps into the ground, bringing just the right conditions to bear. Avid morel hunters begin really scouting once the nighttime soil temperatures remain above 40 degrees for four days in a row, with a couple days of high temperatures above 70 degrees. Some more aggressive hunters may be out sooner, searching the south-facing slopes where the sun’s angle warms the ground more intensely, in hopes of catching some early-season success.

Scouting morel patches in early spring carries an anticipation rivaled by few seasonal events. Step cautiously when checking your patches, as the young mushrooms in their pinning stage can be impossible to see under the leaf litter and other forest debris. Better to return in a few days than risk disturbing the developing fungus.

The morel’s honeycomb-pitted cap is a distinct shape and form, and aside from the wrinkled cap species of false morels such as Verpa bohemica and Gyromitra esculenta, there are no dangerous look-alikes. The false morels are easily distinguished by comparing the ridges and pits of true morels to the wrinkled brain-like appearance of false morels. Regardless of wives’ tales, folklore, or cooking tricks, none of the false morels are safely edible.

In Minnesota, we are lucky enough to have two distinctly different morel species to harvest. The early fruiting black morel, Morchella septentrionalis, appears north of the forty-fourth parallel and comes into season three to four weeks ahead of the yellow, or golden morel. More commonly found associated with green ash or among the bigtooth aspen (especially young, dense stands) in the northwestern portion of the state, it is also sparsely distributed as far south as Houston and Winona Counties in the southeast, where it may overlap with Morchella angusticeps. This species is virtually indistinguishable from septentrionalis aside from being slightly larger, and is widely distributed south of the forty-fifth parallel and east of the Rockies.

The yellow morel, Morchella esculentoides, is both larger and likely a more prolific mushroom in Minnesota. Mostly associated with American elms, they can sometimes also be found with green ash and somewhat less often with cottonwood trees in river valleys. Early fruitings of the yellow morel are sometimes gray and were previously considered a different species. DNA analysis, however has laid to rest this myth. I have long theorized, based on observation, that the mycelium produces different-looking fruit bodies throughout the season: gray morels in the early days, yellow morels in the mid-season, and the legendary bigfoot morels in the waning days.

It is not understood why bigfoot morels grow so large, but I have experimented multiple times by leaving a mid-season patch to mature in hopes that it would develop these giants, only to return to find that the mushrooms didn’t achieve that hoped-for greatness. As exciting as it is to find the season’s first fruiting morels, it can be even more intoxicating to be in the woods when the bigfoots are on. Few harvests can compare to a basket full of bigfoots measuring up to twelve inches, prized for recipes that involve stuffing large caps. Their overdeveloped size doesn’t seem to adversely affect their flavor.

Because morels and their host trees have a mycorrhizal relationship (that is, a symbiotic relationship whereby the mushroom mycelium gives nutrients such as minerals and water to the trees in exchange for carbohydrates and sugars created through photosynthesis) and the morels tend to fruit when that host is dead or dying, patches will diminish over time and eventually stop producing altogether. It’s good to always be on the lookout for new potential patches to keep your morel harvests strong.

An aside: After many years of finding yellow morels in association with dying elms, I noticed that a particular tree might produce morels for several years and then suddenly cease as pheasant back mushrooms appeared. I have never found morels around a tree that produced fruitings of pheasant back, leading me to postulate that the mycorrhizal relationship with the morel mycelium has likely reached its conclusion and a saprobic relationship (that is, one where the host organism has died and is being consumed, often for its cellulose) with the pheasant back mycelium ushers in the next phase of decay for the elm trees.

After a spring rain, morels may be coated in sand and all the spore pockets filled with grit. Sometimes a mushroom brush can’t clear those crevices, so I usually give my morels a quick rinse and shake under cold water, then lay them on a kitchen towel to dry before cooking or dehydrating.

To stuff large morels, trim off the stems and chop them up. Mix some tangy goat cheese with chopped picanté peppadew peppers and a generous amount of finely chopped toasted pistachios. Spoon the filling into a plastic or pastry bag so you can pipe it into the mushroom caps. Arrange the stuffed caps in a baking dish, snugging them together. Cover with foil and bake in a 375-degree oven for about 40 minutes, uncovering halfway through. Meanwhile, cook the chopped stems in butter, stirring often until tender, then simmer with some white wine and a splash of heavy cream. Season to taste. Spoon over the tender mushrooms. Garnish with toasted pistachios.

Journal Entry May 21, 2013 Location: REDACTED

Temperature: High 65 degrees—cloudy—.07 precipitation

Traveled south of the Twin Cities metro looking for morels. Temperatures lately have been wildly fluctuating. Only a week ago it was 98 degrees, and we have gotten more than three inches of rain in the past three days. After a couple dozen empty stops, we finally got into a line of elms that were producing nice-sized yellow morels. With hopes lifted and a good start at real numbers filling my baskets, we decided to drive to a spot that tends to hit a bit later in the season, but I was curious if all the rain and the nearly 100-degree day last week would move things along. Sure enough, my hunch paid off, and soon we had filled every basket, bag, and bucket in my truck. With morel season off to a stellar start, we headed home to begin the tedious task of cleaning and cooking or drying our prizes