21st-Century Farming: It’s Local

Think of the lettuce and leafy greens available in a typical grocery store. The usual selection includes sad, limp iceberg and romaine with rust around its edges. Even the packages of baby kale and spinach with spring mix are past their prime; they were probably transported across the country for several days via truck.

Now imagine produce with names like Red Russian, Orange Fantasia and Blue Scotch. They range in color from light green to deep maroon with tastes from sweet and buttery to peppery and crunchy. Innovative farming methods are making it possible for greens such as these to be available not only in fancy gourmet markets but ultra-locally, even for consumers in urban food deserts.

“The best thing in the morning is spicy arugula on a bagel spread with cool cream cheese. It’s just a great combination,” proclaims Demario Vitalis, owner and operator of New Age Provision Farms. “We grow many different varieties of herbs and leafy greens. For instance, we have four kinds of basil, three varieties of kale and a lot of lettuces.”

New Age Provision Farms unassumingly looks like a couple of large shipping containers sitting on the prior site of an Eastside Indianapolis used-car lot. It is actually a thriving produce farm at the forefront of a new brand of agriculture. The operation is an example of vertical farming at its best, fulfilling a long-term goal for Vitalis.

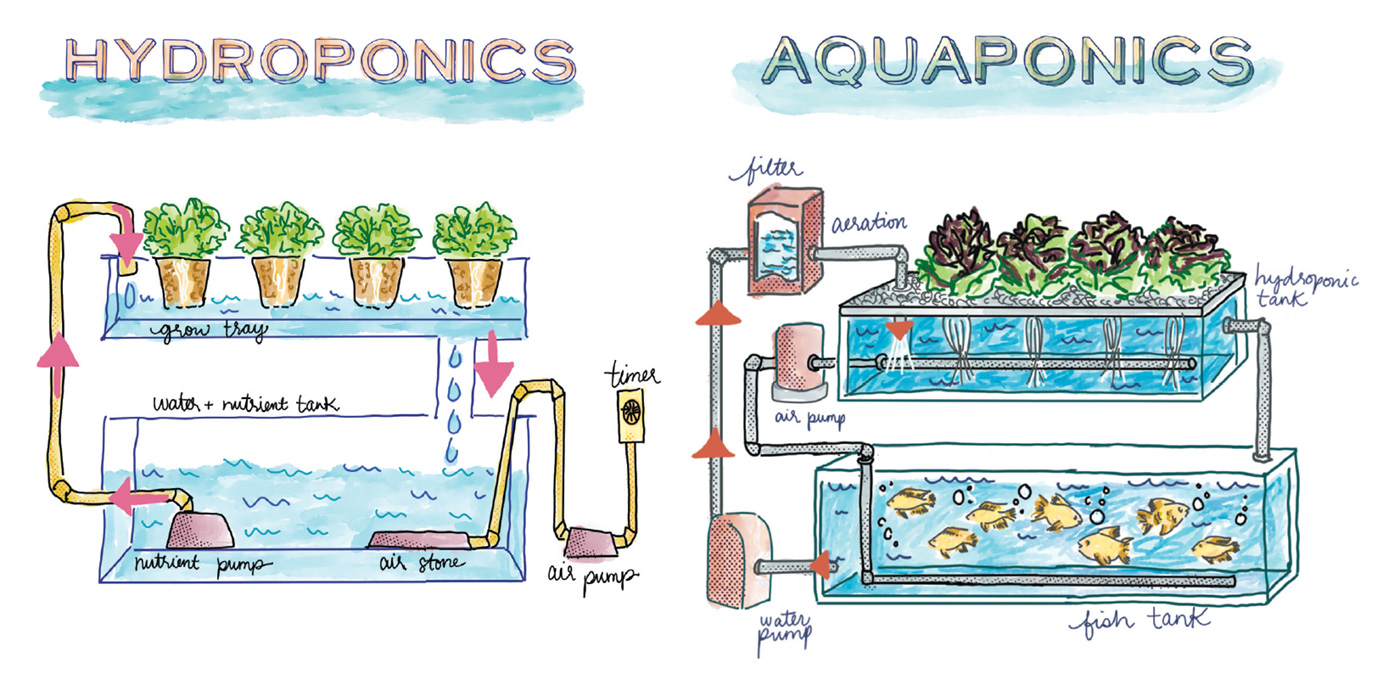

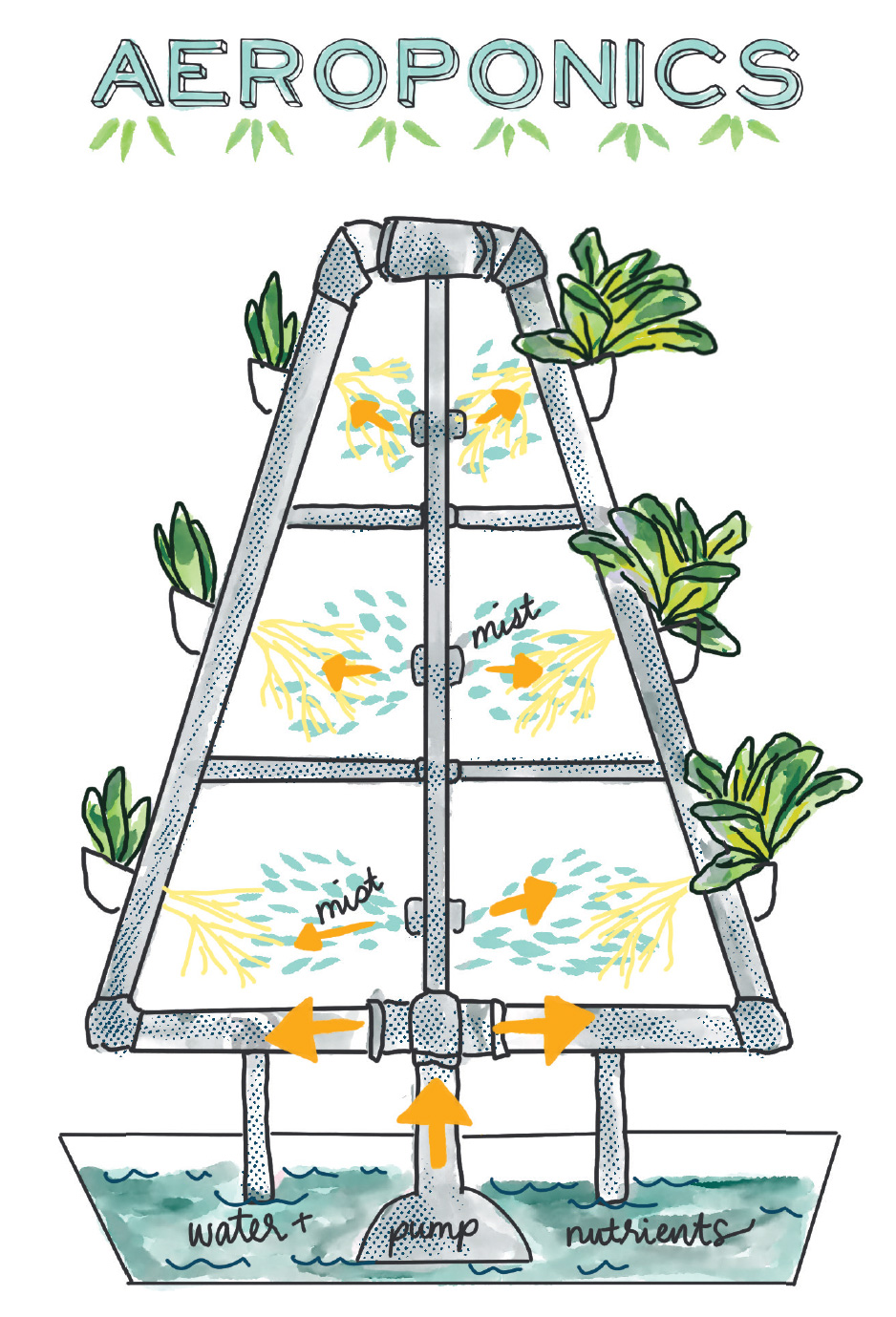

Vertical farming is an umbrella term for several ways of growing crops without traditional farming methods. Since it produces yields without soil, pesticides or the usual fertilizers, it can be found both in urban areas and in remote spaces such as a storage unit in a country barn. Typically, it relies on vertically stacked plant layers flourishing in a controlled environment that monitors temperature, artificial light levels and nutrients.

Vitalis comes from a long tradition of farming; he is the direct descendent of sharecroppers and enslaved African Americans from Mississippi. He wanted to be involved with agriculture, but that seemed impossible without acreage, or the experience needed to farm. Then he discovered the idea of vertical farming within freight containers.

“I started doing my research,” he says. “There are several companies in the United States that sell shipping-container farms. I chose to work with Freight Farms because of the high yield per square feet using the five-channel growth tower configuration and the advanced technology. The system is especially good for new farmers like myself. I can use an app on my phone to control the environment and nutrient levels inside such as temperature, humidity, pH and EC. It has really helped with the learning curve,” Vitalis explains.

“Each shipping container is 40 feet long and 10 feet high. I got the first one in August of 2020 and the second one in January of 2021. The newer model is changed because of upgrades from what the company learned from past experience with previous models. There are changes to the location of nutrient dosing tanks, increased air fl ow and improved lights,” he says.

WINNING OVER THE CHALLENGES

Besides being the first person in Indiana to own a Freight Farms Greenery, Vitalis is also the first African American to purchase a Greenery, he says. In order to make it happen, the Purdue graduate with an MBA from Wayne State University found himself jumping over some hurdles. Although he had creditable experience in business, his first micro-loan application to the U.S. Department of Agriculture was denied by the Farm Service Agency. Instead of giving up, he appealed the decision, and was successful in achieving the loan.

Later, he found out that each container was required to have its own separate electric meter base, which he was obligated to build. Additionally, two 250-gallon water tanks housed in a shed at the back of the parking lot had to be installed. For Vitalis, the resulting farm is worth the efforts.

“The beauty of hydroponics is growing plants without soil. Needed nutrients of nitrogen, potassium and phosphorus are dosed in the water tanks. The system uses two types of hydroponic methods to grow plants. The ebb-and-flow method is used at the seedling tables and the drip system is used for the growth towers. The LED lights shine only blue and red light, and we can control the amount of light intensity. It is estimated to produce the equivalent of seven acres a year. It all comes down to how you use it and what you want to grow,” says Vitalis.

“There are crop cycles going all the time. Each row is staggered. We sell through Market Wagon, Hoosier Harvest Market and the New Age Provision Farms website. Vertical farming provides the solution of providing fresh food to our communities,” he says.

Food can be grown in greenhouses, on vertical farms or as part of edible landscapes.

ANOTHER SPOKE IN THE UMBRELLA: AQUAPONICS

Aquaponics was the answer for Lamar Chupp and his wife, Kristine, who had the desire to farm but access to very little land. This method recirculates purified water that fish have been raised in to nourish produce grown vertically. The Chupps’ farm, Alive! Aquaponics, produces 400 to 500 heads of leafy greens per week that supply area restaurants in Nappanee and Warsaw plus their family variety store, Daily Bread Market in Bremen.

“I first heard about aquaponics when I was a tour guide in Colorado,” says Lamar Chupp. “One night I got in a conversation with some college students. They were talking about how aquaponic systems use 10 percent of the water that traditional soil farming does and that it strikes a perfect balance through the symbiotic relationship of the fish and produce.”

He continues, “I thought I’d really like to try it especially since I only owned four acres of land and didn’t have a lot of room to conventionally farm. I contacted Purdue University for help. Some commercial parts were ordered but most of the operation was built from scratch.”

On one side of the farm there are four fish tanks, each housing Blue Tilapia in different stages of maturity. Water is converted to nitrogen-rich liquid feed before being pumped over to the produce. Planting and harvesting occur every Wednesday in a six-week cycle. The resulting harvest is red- and green-leaf romaine, butter lettuce, kale, bok choy, Swiss chard, kale and French crisp. After reaching maturity, the fish end up on the tables of family and friends.

The experience inspired them to develop a hydroponic unit that takes up no more space than a residential dishwasher.

21ST-CENTURY HOME FARM

While Vitalis and the Chupps are focused on localized vertical farming for communities, GroPod© is the next-generation personal vertical farm for home use. It is a product designed and distributed by Heliponix©™, a company co-founded by Purdue University graduates Scott Massey and Ivan Ball. The two met while working together on a NASA-funded research project that investigated using red and blue LED light in controlled food growth environments. The experience inspired them to develop a hydroponic unit that takes up no more space than a residential dishwasher. Massey believes this is the future of farming.

“We need to reinvent agriculture. Our nation is producing food at its full capacity, yet 40 percent of it is thrown away because it spoils before it gets to the consumer. Traditional farming methods use 50 percent of our land, take up 80 percent of our freshwater consumption and are the cause of 70 percent of our water contamination through runoff after the use of fertilizers and pesticides,” he says.

“Our nation grows plenty of food, but it goes bad over time. Produce loses half of its nutritional value in even the first few days after it is picked. Plus, we are reaching our production limits due to diminishing land and water availability. Hydroponics in general, in which nutrient-rich water is recycled over plant roots and uses 90 percent less water with no pesticides, is the answer for 21st-century methods,” says Massey.

The GroPod uses aeroponics, a subsystem of hydroponics that uses less water. Growth begins from seed pods that look similar to coffee pods to grow up to 60 plants at a time. An app is used to view plants via a camera. LED lights enable growth, while ultraviolet light kills any bacteria, viruses, fungus or mold that may develop. Only eight gallons of water are used each month on average. The result for the consumer is vitamin-rich leafy greens and produce that remains alive until the moment it is picked.

“Seed pod subscriptions are renewed monthly and can be adjusted to suit an individual’s or family’s needs. Although a GroPod could be installed anywhere in a home, produce is already stored in near-equivalent spaces in the kitchen. Why not utilize it to grow and enjoy superior quality of flavor and nutrition through maximum freshness?”

ENABLING OTHERS, SHARING KNOWLEDGE

Robert Colangelo, founder and CEO of Green Sense Farms located in Portage and host of the national radio show and podcast “Green Sense,” was an early adopter of vertical farming. He has been dedicated to the environmental industry and started his career working on a wide variety of environmental research projects at Argonne National Laboratory, moved into engineering consulting (remediating contaminated soil and groundwater at industrial operations) and then started a company to buy, redevelop and sell brownfield properties. Colangelo turned his sights to Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA) to farm sustainably. In 2010, Green Sense Farms began building what was at that time the largest indoor vertical production farm in Portage to grow and sell leafy greens to grocery store chains and produce companies in northwest Indiana and areas close to the state border.

“A big part of vertical farming is the focus on sustainability,” he says. “In my mind we had to do more than just clean up these brownfield properties and had to stop creating them. By building green projects on the remediated brownfield sites, new operations would have little impact on the soil and water. In vertical farms, more crops can be produced with less impact on the environment. Crops can be grown year-round, free of pesticides, using tap water to mix with fertilizers that can be recirculated. The future of farming will be limited by the availability of arable land and good-quality water. We have to get better at managing these resources in order to feed a growing global population.”

By 2018, Green Sense Farms pivoted its business model and focused on contract research, horticulture consulting and the design and build of CEA farms. Today, the company focuses on providing expertise to a wide range of clients from Fortune 5000 companies interested in conducting research to grow crops indoors to entrepreneurs and investors looking to enter the new emerging CEA market.

“Cracks in the supply chain were exposed during COVID. Prior to COVID, no one really paid attention to the fact that 90 percent of lettuce comes from Salinas, California, in the spring and summer and then Yuma, Arizona, in the fall and winter. Both are drought environments, yet millions of acres of lettuce, which is 90 percent water, is grown there. Then the lettuce is shipped by truck for days across the country. It’s not always as fresh as people want it to be,” says Colangelo.

“People would now like to be closer to their food,” he continues. “Green Sense Farms just launched a new initiative focused on mixed-use agri-centric developments where industries like resorts, hotels and hospitals can create experiential destination centers, focused around food production. Food can be grown in greenhouses, on vertical farms or as part of edible landscapes. For example, hospitals can set up greenhouses or rooftop farms to grow fresh and nutritious produce that can be used in meals to help heal their patients.”

SOURCE FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

Six years ago, after multiple decades of participating in the New York real estate brokerage field, Herbert H. Kliegerman became interested in the push to localize and reinvent traditional agriculture. He started a digital platform, the iGrow Network, that has become an encyclopedia for researchers and those interested in expanding knowledge in the growing shift away from traditional agricultural methods. Its data base includes international articles about a new breed of 21st-century growers, including the Indiana growers mentioned in this article.

“The COVID pandemic raised consciousness about healthy food,” says Kliegerman. “At the same time, there has been a response to climate change. California, where most food in the United States is raised, has been affected by drought and fire. Why buy something shipped when people can get something that was raised around the corner? Alternative methods to traditional farming such as those developed by GroPod and Green Sense Farms are here to stay.”

NEW AGE METHODS? THINK AGAIN!

The most legendary vertical farm may be the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, constructed more than 2,500 years ago, in which vegetation grew on stacked terraces watered from a pool at the top.

Maya and Aztec farmers in Mexico grew crops on floating farms on Lake Texcoco, taking advantage of nutrients produced by aquatic creatures living beneath.

Ancient farmers in China, Indonesia and Thailand grew rice in paddy fields that were fertilized by wastewater coming from cultivated fish farms.

For more information on the vertical farms mentioned in this article, visit:

- New Age Provisions: NewAgeProvisions.com

- GroPod: GroPod.io

- iGrow Network: iGrow.news

- Green Sense Farms: GreenSenseFarms.com

- Alive! Aquaponics (no website); call 574.646.2054