Breaking Bread

Butter, jelly, garlic, tuna fish, PB&J, salted butter … really, what would any of these classic spreadables be without a proper taste bud delivery vehicle? And, what taste carrier is more traditional than a perfect piece of bread? I confess that I refer to bread as just a vehicle for sweet, salty, softened butter (and keep your Paula Deen jokes to yourself).

As the country and our state change into an ever-more-diverse multicultural melting pot, Hoosiers are getting the flavorful fallout of everyone’s traditional foods. Here in Indy, we now have all-you-can-eat sushi on the west side, tagine near the monuments and haggis on Mass Ave. But one thing that remains a mainstream food is the bread brought to America during a time that spanned hundreds of earlier years.

Many of us can trace family back to European immigrants who came to the continent between the 1600s and early 1900s. They brought with them the knowledge of leavened bread, made with the recipes handed down to each maker by their relatives back in the old country. Loaves were hand shaped and baked to practiced perfection, then fed to the family after a long day of the physical labor necessary to keep a household together in those days. (Yes, take-out pizza addicts, even here in Indiana life was not easy.)

As we moved into the industrial age, through the Great Depression and two World Wars to the age of prosperity, our food habits changed along with the times. Mechanized food production cut down time the “lady of the house” spent in the kitchen. Advertisers made us believe a woman’s life would be perfect if she obtained a starched apron, a set of pearls, a Perm-N-Curl and a giant new stand-alone freezer … with stacks of frozen dinners stored inside.

Loaves of bread were made available pre-baked and wrapped in plastic decorated with large yellow, red and blue dots, awaiting us on the grocery store shelf. And if your mom was a winner, your square sandwich even came delivered to your place at the kitchen table sans crust. It seemed the days of making bread by hand as part of our family traditions were over for anyone with enough take-home pay to drive the giant family car or send the kids down to the supermarket to pick up a pre-sliced loaf.

Somewhere along the way, not so long ago, we began to reconsider all that we had lost—flavor, texture, nutrition—in our pursuit of convenience. Somewhere in a kitchen or restaurant, someone made a lovely loaf of crusty bread (you know, the kind without a pre-sliced layer of gummy, garlic-infused yellow paste that went into the oven for spaghetti night). And someone, somewhere, received the gift of eating that bread with its maker. (And if they were really thinking, they hit that loaf while it was warm with two plates, two knives and a pound of soft, salted butter! Sorry … where was I? Oh, yeah ...)

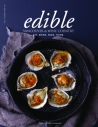

Bread. Tradition. Meet Alexa Meadows and her mom, Irina Zuevich, whom I met during a recent photo shoot for Edible Indy. Alexa makes sweet and savory baked foods (which make tiny angels sing inside my head) and sells them through her Fishers-based company, La Torte Bakery. While we chatted all things food, and about the quirky life of

a food photographer-slash-college-student (yes, me), we got on the subject of traditional European breads and I found myself invited to the home of these warm and lovely Eastern European women to talk, eat and photograph some of the traditional breads they make.

My afternoon in their kitchen was filled with hospitality, laughter, the wafting scents of baking and cooling breads and the sharing of family history. One thing about bread is that it is one of the world’s great time-stoppers. As we sat with cups of tea and one of Alexa’s cakes (which nearly brought tears of cake-loving joy), I realized this was what the old sages meant when they coined the term “breaking bread.” A few minutes of life at a slower pace, and an Old World tradition of sharing something made with love and care, gave us time to talk, laugh, exchange.

Alexa and Irina are from Kyrgyzstan, one of the formerly Soviet republics that lies against the Chinese border. Though they are Russian, they consider themselves Asian by cultural influences. They also happen to be versed in many of the foods across the European continent.

Irina, a skilled cook and baker who passed her knowledge on to daughter, Alexa, found herself in a difficult situation in the early 1990s. After the fall of the USSR, nearly everything, including food, was in short supply. Only one ingredient stayed steadily available: flour. Irina became an expert in bread baking. Not just their local traditional breads, like bulocka and bauraski, but bread from other countries: Italy, France, England.

Breaking bread is communion in its truest form. The motion and action of sharing a traditional loaf of bread with someone else brings community. At that moment, at that table, we were a community of three. Learning about each other and our cultures. Discovering what brought them to Indiana, and what makes us so alike despite the thousands of miles between our childhood homes. In this case, European bread was our common thread. I’ve spent years making it because I love the art of the process; Irina spent years making it so her family would be safely fed each day.

Old World bread takes time and some practice. Irina made three loaves for me that day, all made by hand: a light brioche, a French baguette and an Italian loaf.

The starter for her Italian bread had been sitting for 48 hours and dough had been proofing for eight. After shaping loaves and letting them sit for an hour, then one more hour in the oven, this pillow of Italian heaven had been up to 56 hours in the making. And pulling apart the buttery brioche, I’m pretty sure I heard those little angels inside my head singing again … or were they just whispering to me that I should smash my face into the loaf and eat from the inside out? Lucky for all of us, my politeness filter kicked in, and I refrained.

We talked for a while about the bread making process and agreed nearly anyone can make a good loaf of European bread, either by hand, with a trusty kitchen mixer or with a bread machine. With a little practice, anyone with the desire to make a classic, traditional loaf of European bread can have beautiful loaves to eat all winter. Just in time for soups, casseroles and the stick-to-your ribs foods we crave when the weather gets bad and we need comfort. European breads were created to go with all of the foods we want when the skies are spitting frozen water and we stare out the window wishing for just one green leaf.

I would love to see everyone try his or her hand at making traditional European bread. The process is slow, but not difficult. Practice makes perfect, and every loaf that comes out of the oven is a victory and a moment to cherish. And sharing that loaf with others gives us a personal connection that’s hard to find in any other way. Start by making a loaf using one of the two recipes below. Make it two or three times and you’ll find yourself addicted to the process, and to the smells and to the sharing of bread with others. And while you’re noshing on your beautiful bread, don’t forget to listen for those angels.

Mary McClung resides in Indianapolis and is senior at Herron School of Art & Design, completing her BFA in photography and intermedia. Her art and professional work includes photography and video. Mary’s love for the slow, sustainable, farm-to-table culture manifests itself through her work photographing and promoting the food and the food community in the Indianapolis area.