FROM BUTCHER TO RANCHER

Barbooth. It sounds just like it’s spelled. But while it might be phonetically easy, the meaning is a little bit harder to figure out, as it has nothing to do with a bar, or a booth for that matter.

“My grandfather won $65,000 playing barbooth,” says Fred Linz of his grandfather, Martin Linz, who eventually used the money to open his butcher shop, Linz Meats, in the early 1960s.

Playing what? Playing in a bar? In a booth? In a butcher shop?

Barbooth, also called barbotte or barbudi, is a Middle Eastern game traditionally played with miniature dice … and though it can be played in a bar, it’s also played in many homes throughout Greece, Turkey and other countries in the region. Here in the U.S., it’s a game people often play with hopes of winning money. Of course not everyone is as fortunate as Martin Linz—today, that $65,000 would have roughly $538,300 in purchasing power. And Linz, so it would seem, was set— financially at least.

“His parents passed at early ages and he raised his siblings,” says Fred, so there was no time for special training. No business degree. No extra schooling in anything other than the school of hard knocks.

“Marty at one time worked in the meat department at Goldblatt’s in Hammond,” says Fred, which presumably gave him both the skills and the desire to open his own butcher shop.

And so, with meat purchased from Chicago distributors, Martin Linz opened his shop in Calumet City, Illinois, and before long, not only was he providing high-quality meats to friends, family and surrounding neighborhoods, he found himself supplying nearby restaurants too.

Now, more than 55 years later, Martin’s butcher shop is known simply as Meats by Linz and is a top supplier of lamb, veal, poultry, pork and their signature Black Angus beef cattle.

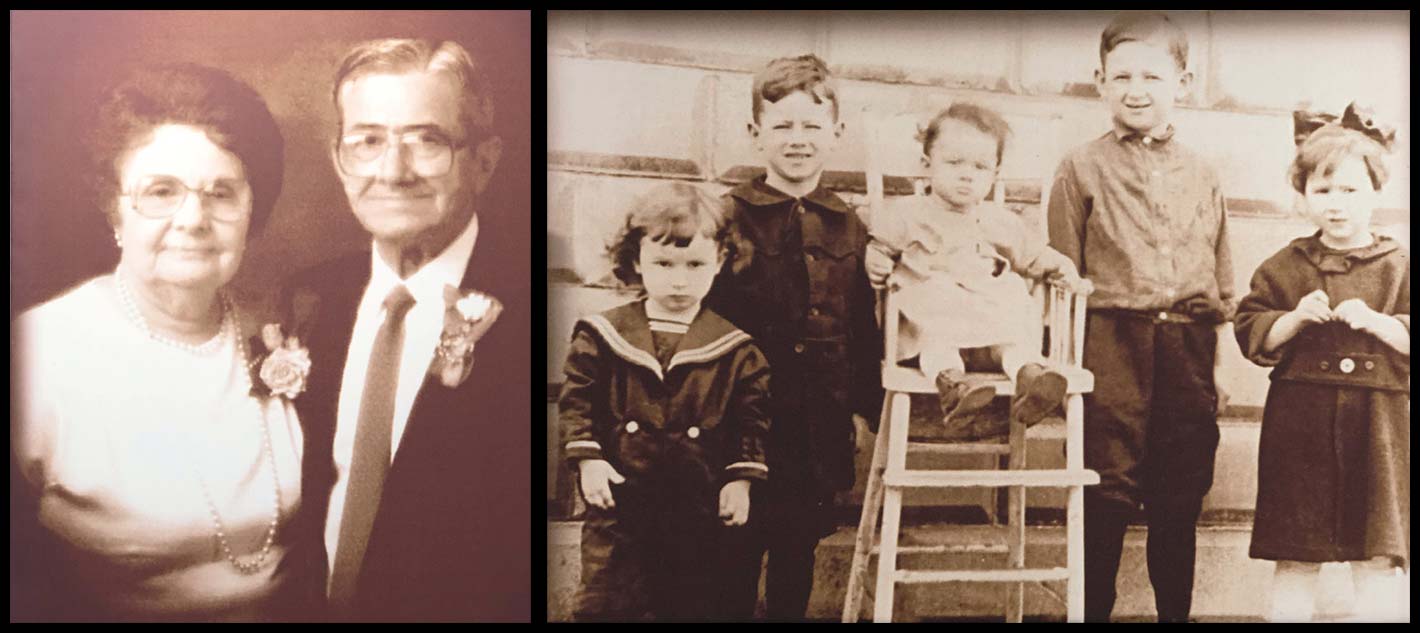

Martin (Marty) Linz (second from the right), patriarch of the Linz family business, with his siblings. Left: Fred Linz’s grandparents, Francis and Marty Linz.

LAUNCHING A BRAND

In an effort to control quality of product, in 2013 Linz started the family’s namesake brand of cattle program, Linz Heritage Angus (LHA). “We started with 10 first-calf heifers with calves at their side, and currently have 1,100 registered animals for breeding and genetic development.”

To develop the Linz Heritage Angus Genetically Verified cattle, they work directly with other ranchers who agree to work within their set of strict guidelines.

“The partnered ranches are large cow-calf operations that use LHA bulls in their breeding programs to breed their females by either natural or artificial insemination. These cow-calf operators must use pureblood Angus females,” Liz says.

And it’s this control over genetics that ensures Angus is bred with Angus, and that every female is a third-generation Angus blood.

“There is much better genetics in the Angus breed today,” says Linz. And it’s the better genetics, he says, that produce a higher-quality product and better eating experience for the consumer.

Of course there’s more to raising cattle than genetics. There’s the everyday care and nurturing that goes into raising the animals—care that includes making sure the herd gets proper rest, exercise and feed.

“We humanely raise our cattle,” says Linz. “They are turned out on pastures from spring through fall,” and, he says, they’re fed a variety of both grasses and hay throughout the year. Eventually, the cattle is corn-finished, which creates what the Linz family says is the “wow” steak-flavor profile and superior marbling that has earned their product a place in some of the top steakhouses in the country including St. Elmo, Harry & Izzy’s, Manny’s, Ditka’s and many more.

“One of the many reasons Angus are so popular is because of all of the things they do so well as a beef animal. From a farming perspective the Angus cow combines the best mothering ability with some of the best traits in the industry for calving ease and growth. From the meat side they are superior in producing high-quality, great-tasting meat that is demanded by the consumer.” —Casey Jentz, American Angus Association regional manager for Illinois, Indiana, Michigan and Wisconsin

WHAT LIES AHEAD

As for the future of cattle farming, Linz has his concerns.

“Cattle farming seems to be losing interest from the next generation,” he says. “They’re getting degrees and taking positions in society off the farm and more in corporate America.”

But this fourth-generation family-owned and operated company, which still insists on hand-cutting the majority of steaks and eyes-on inspection of cattle, hopes its LHA program will prove superior and continue to give consumers the best beef money can buy.

“Starting the LHA program is something we feel separates us from the norm. We want to provide our customers [with] the very best product we can. We want them to have something the competition does not,” and says Linz, they do this by tying a story—their story—to the product.

BOVINE ABCs

Heifer: A female bovine that has not borne any calves.

First-calf heifer: A female that has borne her first calf.

Calf: A male or female less than 1 year old.

Cow: A general term for a female that has borne one or more offspring.

Steer: A male that’s been neutered.

Bull: A mature male used for breeding.

Cattle: Can be used to describe both male and female bovines.

Linz Heritage Angus works with family farms across the Midwest. Fred Linz is pictured far left.

OPEN DOOR, OPEN BARN

Transparency on the Farm

At Linz Farms, they pride themselves in humanely raising their animals and employ an open-door policy where anyone can visit their farms and pastures.

“All of our animals are treated as if they are part of our family,” says Fred Linz.

“We provide the best care and living arrangements possible, from beautiful open pastures to calving barns during the cold winter months. Our animals,” he says, “are our bread and butter. If they are not in their best performing conditions we cannot progress with our program.

“We have a staff of six employees that care for approximately 1,100 head,” he says, and to ensure the animals are in top condition, they perform daily health checks.

“There are eyes on each animal every day,” he says.

And though animals on his farms are nurtured and properly cared for, sadly, this isn’t the case for all farms here in Indiana, let alone across the country. According to the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) there are more than nine billion land animals raised for food in the U.S. each year, but there are no federal laws directly protecting the animals on farms; in other words, the methods in which they’re raised are not federally regulated. There is a law in place, however, covering the transportation of animals and The Humane Methods of Livestock Slaughter Act requires livestock “be quickly rendered insensible to pain before being slaughtered.”

Why no federal laws on the actual raising of animals? Some advocacy groups claim it’s “big ag” and right-to-farm bills that are keeping us from having complete transparency on the farm but over the last few years—especially with recent news stories of horrific animal abuse and inhumane conditions— there is a push for an open-barn policy across all segments of livestock farming.

Certain groups, like the Global Animal Partnership, The American Humane Certified Program, A Greener World’s Certified Animal Welfare Approved and others, have a list of “best practices” for animal care. The criteria—established by scientists, veterinarians, farmers, educators and researchers alike—vary somewhat between organizations but they all have one goal in mind: to insure the animals are properly cared for throughout all aspects of their lives.

In January 2017, stronger animal welfare standards were released by the USDA Organic program, but by the end of the year, the agency had announced its intention to completely withdraw the new standards. The ASPCA is actively monitoring the progress or lack thereof through the ASPCA Advocacy Brigade. Visit its website, ASPCA.org, for more information.