Changing the Cup

Greg Hardesty

On a Sunday morning in early 2020—just weeks before the COVID-19 pandemic washed across American shores—a group of 20 or so individuals gathered around four-top tables reconfigured into a large rectangle in the main seating area of a storied dining institution in Columbus, Ohio. The restaurant would open later that day for dinner service.

Normally this collection of souls—young, old and from varied walks of life— would be at work in kitchens, behind bars, punching away at computers in business offices at the city’s leading hospitality groups, or moving swiftly across dining rooms to serve patrons at institutions like this one all over town.

On this day, however, the group sat somewhat solemnly at tables more accustomed to the sight of hungry smiles and the sound of daily specials being recited. Some participants appeared tired, others alert; many seemed eager to talk, keen to engage with the room; all were at least ready to listen.

“My manager told me to come here,” a blonde young woman told the collective through tears when it was her turn to speak. She said that she drank too much the night before, adding that most nights she makes this same mistake. “I don’t know how to stop,” she continued while a friend squeezed her hand. Sometimes, she said, when she’s well past sober she’ll add a drug or two to the mix.

This was a meeting of the Columbus, Ohio, chapter of Ben’s Friends. The organization, which has representation in 14 cities and counting, was founded in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2016 by restaurant veterans Mickey Bakst and Steve Palmer in honor of their late friend, Chef Ben Murray, who committed suicide after a long struggle with addiction and depression.

The organization bills itself as “the food and beverage industry support group offering hope, fellowship and a path forward to professionals who struggle with substance abuse and addiction.”

“It took me a long time to realize what the reality of being an alcoholic entailed,” one member of the Ohio meeting said above the clamor of pots and pans in the background from a lone cook setting up for the day.

“Alcoholism was an excuse to do whatever I wanted,” another participant added. She then calmly told the group to try one of the red velvet cupcakes, donated by a much-loved bakery in the city, displayed amongst an impressive spread of snacks and coffee in the back of the room.

“We don’t mess around with the treats here,” another member added while the room erupted in laughter

The industry now appears ready to talk openly about the addiction and mental health issues that have long plagued the sector.

An Industry Epidemic

Andy Smith launched the Columbus, Ohio, chapter of Ben’s Friends in September 2019 in consultation with the group’s national organizers and with help from Cameron Mitchell Restaurants. Smith had faced his own battle with addiction while watching friends in the industry fall to the disease.

“I’ve never met Ben, but I’ve got 20 of them,” Smith says about Murray, the inspiration for the original Ben’s Friends. “Everyone in this industry has a Ben.”

After only six months, the fledgling Columbus chapter faced a massive challenge with the arrival of the coronavirus pandemic in March 2020 and its economic impact on the food and beverage industry. Smith calls initial shutdowns of the sector a “shock.” However, Ben’s Friends forged ahead with online engagement, bringing participants from across the country together daily to connect on sobriety.

“It just took off and I’ve gotten to know so many people,” Smith says about new friends in California, Washington and Arizona, with whom he connects regularly at the organization’s more than 20 Zoom offerings each week. “I’m excited for when we go back to in-person meetings, but I also hope we hold on to Zoom because it’s turned into something really cool, too.”

A 2015 study from the U.S. government’s Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration found that the food service industry has one of the highest rates of substance abuse in the country.

“The highest rates of past month illicit drug use were found in the accommodations and food services industry (19.1 percent),” the authors of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health wrote, referencing data collected from 2008 to 2012. Additionally, the authors noted that “workers in the accommodations and food services industry (16.9 percent) had the highest rates of past year substance use disorder.”

Many in the sector point to late nights, long hours and demanding work environments as fuel for the epidemic’s bright fire. Others identify a culture of not only excess but access—with alcohol easily accessible before, during and after a shift.

Nearly three years after the suicide of Anthony Bourdain, beloved American celebrity chef, writer and television personality, and 20 years after the publishing of Kitchen Confidential, Bourdain’s memoir profiling his “25 years of sex, drugs, bad behavior and haute cuisine,” the industry now appears ready to talk openly about the addiction and mental health issues that have long plagued the sector.

Additionally, with 2020’s health, social and economic crises—a perfect storm disproportionately impacting low-wage American workers—the food and beverage sector has faced a year unlike any other with crushing stress and uncertainty. For some, these elements have further fueled addiction’s tumultuous fire.

Greg Hardesty, owner of Indianapolis’ Studio C, former owner of Recess and allaround beloved capital city chef, has worked in restaurants for nearly 30 years. Twenty of these have been devoted to fine dining in Indiana’s capital.

“I think the industry certainly fuels it, enables it,” Hardesty reflected pre-pandemic on rampant substance abuse in the sector. “We almost reward somebody for coming in and working through a hangover. ‘You’re a badass,’ we say to them.” This January, the chef and entrepreneur celebrated four years of sobriety.

Smith said he initially thought his problem was restaurant culture. However, after a court order mandated him to attend Alcoholics Anonymous, which finally pushed him to the other side of addiction, and after attempting jobs in other industries, Smith quickly discovered that “the problem was actually me, not necessarily the industry,” he added. Smith now bartends at Harvest Bar + Kitchen in Columbus’ Brewery District while also operating his own consulting business focused on sobriety in restaurants. He calls the cliché of the drunk, coked-up bartender “outdated.”

“I remember talking to my friend after I got sober and asking, ‘How am I supposed to work in a restaurant? How am I supposed to sell booze?’” Smith says. “I’m living proof that you can work at a restaurant and sell alcohol.”

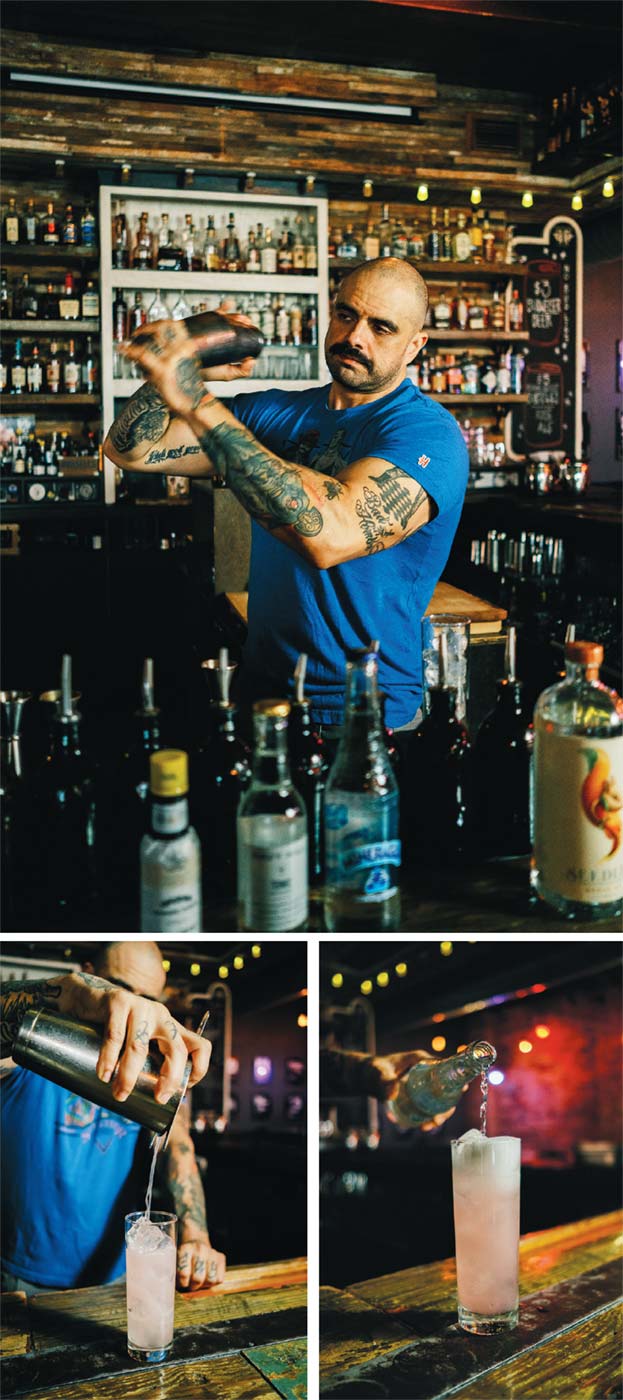

For Joshua Gonzales, owner of Indianapolis-area bars Thunderbird and Jailbird and one of the city’s best-known mixologists, during much of his 20-plus years in the Indianapolis beverage scene he struggled with alcohol addiction. He has been sober now for more than four years.

“For some, alcohol is a way to sustain 12-hour workdays,” he says about the industry’s often-demanding schedule, which can entail noise, heat and long hours on one’s feet. “It’s also a way to sustain social anxiety when you have to talk to 200 people a night.”

“I think the reason that addiction is rampant in this industry is that it’s just very, very normal,” the bar owner says. “Your staff is consuming with you, you’re doing shots during service, you’re having a beer, you’re having a glass of wine, putting bourbon in coffee. You just have access. Access breeds normalization. Normalization breeds problems.”

Hardesty says his addiction hit its peak when his restaurant obtained a three-way license to sell beer, wine and liquor. “Once the leash was taken off hard alcohol, I was drinking it at the same rate I was drinking beer,” Hardesty says. “I just didn’t change the cup I was using.”

“Everyone in this industry has a Ben,” Smith says, reflecting on the rampant addiction and mental health issues prevalent in the sector.

Joshua Gonzales

A New Beginning and a Better Craft

“One of the things I struggle with is some of the regrets,” Hardesty says candidly about his battle with alcohol. “Mainly, regrets about my addiction and my kids.”

“I basically woke up one morning—about 2:30am—my wife asked me if I was alright and I said, ‘No, I need help,’” Hardesty remembers about the fateful day when he finally decided to face his addiction head-on.

Hardesty did a 12-step program, created by the founders of Alcoholics Anonymous, as part of his recovery. Prior to the pandemic, he says he went to Alcoholics Anonymous meetings three times each week.

“I thought drinking made me a better chef,” Hardesty says. However, now that he’s sober, he says that notion has quickly faded.

“It turns out, I’m cooking better than ever,” Hardesty says. “I cook more honestly. I fuss with the food less. I don’t worry so much about intricate plating. It’s more real to me now. I think that reflects in the food I’m serving.”

Studio C is still in operation despite the personal and professional turbulence Greg Hardesty has faced this year (see sidebar). In the spring of 2020, the operating model for the culinary space quickly shifted to a grocery in response to the pandemic.

Reflecting on his battle with addiction, Joshua Gonzales says that he liked the way booze made him feel but it was tied to a deeper personal struggle. “A lot of it was issues that I have with anxiety and self-confidence,” he notes. “The booze helped to calm down those mental and emotional instabilities.” Gonzales says that by the last few years of his addiction he was having at least 20 drinks a day.

Gonzales says that giving up alcohol has made him a better business owner and manager. “At Thunderbird, I don’t have anyone on my staff that knew me as a drinker,” he says. “When I look at how my staff behaved in those years, those that knew me as ‘Drinking Josh,’ it was all very turbulent. The staff was drinking a lot on shift because I was drinking a lot.”

Even with the stresses of the pandemic, Gonzales says he doesn’t worry about slipping up on his own sobriety as he did in the early days of recovery. However, he adds, he leans on friends in the industry to help him get through the hard moments especially during this turbulent time. Those allies are essential to those in recovery, Gonzales says, and he recognizes his responsibility in this capacity, as well.

“I’m 43 now,” Gonzales reflects. “When I was 25 and bartending, I didn’t have anyone around me that wasn’t doing the crazy things: that wasn’t doing blow; that wasn’t doing shots every night behind the bar; that wasn’t partying until 4am every morning. That was just life. I now think that having people around you that show an alternative is beneficial.”

Gonzales says leaders in the industry—whether it’s a bar or restaurant owner or a manager or veteran at a chain—have an incredible responsibility to those coming up under them. “We need to make sure those people that work for us are in a better position than we were when we were their age,” Gonzales remarks. “If we don’t do that then we’re doing a disservice.”

Gonzales is forging ahead with business as usual at Thunderbird and Jailbird despite COVID-19. He says though there have been hard days during the pandemic, the disruption has confirmed the important role that institutions like his play as gathering spaces. “People need to socialize and feel community,” Gonzales says. “My commitment to making these businesses successful again and maintaining their life cycle has been reaffirmed.”

Back in pre-pandemic Columbus at Ben’s Friends, the group neared the end of one of its last in-person meetings before COVID-19’s arrival. A woman several decades older than the girl who shared that she drank the night before was one of the last to speak. She had matching fair features and blonde hair; the two could pass for mother and daughter.

The older woman looked directly at the younger one while she spoke. “I drank last night too,” she said, explaining that, like most nights, she drank half a bottle of wine after arriving home from her restaurant shift. “I wish I could stop.”

“I also wish I had the gift of time,” she added, nearly willing the younger woman the decades that have slipped away to addiction. Both women cried; sniffles from the group could be heard echoing off the dining room walls.

“I was lying in bed feeling sorry for myself,” the older woman said about that morning, just a few hours prior. “I logged onto Facebook and found Andy and news of today’s meeting,” she added, her gaze turning to Smith, seated nearby.

“I just want peace,” she said assertively, optimistically, in a voice that had been quivering only moments before. Across the room, heads nodded in appreciation, the group welcoming her to their fray.

Finding Support

If you work in the restaurant industry and are struggling with an addiction or mental health issue, here are several resources that may assist you: Ben’s Friends is a Charleston, South Carolina–based organization offering hope and fellowship to those in the food and beverage space struggling with substance abuse and addiction.

The organization has chapters in 14 cities across the country. There is not yet a chapter in Indianapolis but there is a need. If you’re interested in launching one locally, reach out to the organization’s founders via their website to express an interest. bensfriendshope.com

Chefs with Issues is devoted to the “care and feeding of the people who feed us” and offers a website with a slew of resources and reading on addiction and mental health. The group also has a very active private Facebook group where conversations on addiction and mental health are undertaken daily. chefswithissues.com

Indianapolis maintains active Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous chapters where members from all walks of life, not just the restaurant industry, engage on addiction and recovery. indyaa.org, centralindianana.org

Finally, if you are struggling and need immediate assistance, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, a toll-free, 24/7 hotline available to anyone in who is suicidal or in emotional distress. 800-273-8255

Greg Hardesty’s Health Battle

In July 2020, Greg Hardesty was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. In November, he was scheduled to have a stem cell transplant after undergoing chemotherapy. The procedure fell through due to the loss of the donor.

“The goal was to get me into remission with chemo and then have a stem cell transplant,” he explains. However, his journey has included the return of the cancer— yet again delaying a transplant—and in January he began his first of two rounds of immunotherapy. By March, he says, his doctors hope he will once again be in remission and the needed transplant can occur.

“Much of the pandemic I’ve been dealing with this,” Hardesty says about his cancer diagnosis in this most unusual time. However, he remains optimistic, he says, and the shake-up in both his personal and professional lives has helped him to reprioritize.

“I’ve been in this business for 30 years and I had gotten somewhat burned out,” he says about growing dissatisfaction in his work as a chef in the years and months prior to the pandemic and his life-altering health diagnosis. The changes to Studio C’s operating model due to the pandemic and Hardesty’s health struggles have opened his eyes to potential opportunities on the horizon. “The idea of being more of an entrepreneur and less of a chef now excites me,” he adds about the next phase of his career.

Hardesty says he’s also focusing on his wife and children at this important time as their support has been a bedrock for his battle with cancer. During his initial treatment, his wife visited him daily despite COVID-19 restrictions as she worked at the hospital where he was receiving care. “I felt pretty blessed,” he says about his time with her during those tumultuous first days of his fight.

To follow Hardesty’s battle and donate to support his care, visit ghf.betterworld.org.