A CHEF’S JOURNAL - A glimpse inside local chefs’ creative process

Glancing through menu descriptions, admiring beautifully plated dishes or sipping cocktails with cleverly conceived names, it’s hard to imagine these culinary delights were once just a glimmer in the eyes of the chefs who created them.

So how do chefs dream up the magic they serve? What’s their inspiration? And how do they capture ideas once they have them?

Edible Indy sat down with three local chefs to ask about their journals, how they gather, brainstorm and store ideas. What we discovered is a creative process that looks different for different chefs, and can evolve over the course of a career.

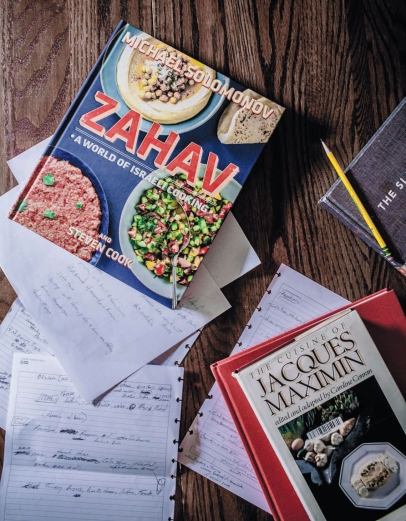

Chef Greg Hardesty scribbles menu notes with his #3 Ticonderoga pencil.

Chef Greg Hardesty scribbles menu notes with his #3 Ticonderoga pencil.

FOLLOWING THE MUSE

Chef’s journals start with gathering what inspires. While ideas can come from anywhere, for veteran Indianapolis chef Greg Hardesty they almost always end up on a sheet of loose-leaf paper scribbled down with a #3 Ticonderoga pencil.

These pages have served as an incubator for nearly all Hardesty’s work over the past 26 years. As an example, one page has the beginnings of a recipe for shrimp dumplings, a dish he later served at the August Chef’s Collective Dinner at Spoke & Steele, where Hardesty has served as creative culinary director since January 2018.

“It starts with a bunch of ideas, then it becomes a little more compact, then it becomes a menu, then it starts to become prep lists, to-do lists, ordering lists, recipes,” he explains.

Not everyone goes for loose-leaf sheets, though. Celebrated chef Jonathan Brooks, owner of Milktooth and co-owner of Beholder, uses bound journals to capture ideas for dishes, draw shapes for cutting vegetables or jot down ingredients he wants to combine.

The bound journals work for Brooks when he’s starting a new restaurant. After opening night, though, he sets them aside, and his creative process becomes more market-driven, based on what farmers are bringing him. At that stage, he “draws and experiments on the plate,” Brooks says.

He’s also an avid cookbook collector, and cookbooks serve as another kind of inspirational journal for his work. “I dog-ear the shit out of my cookbooks,” Brooks confesses. “I’m not protective of them. I’ll buy four or five cookbooks at a time and sit down when I have a free night, and just look through every single page.”

But Brooks’ inspiration doesn’t end there. He loves literature, both fiction and nonfiction, and he marks up the pages of novels or memoirs that might spark ideas for cocktail names or new dishes.

“I’m very inspired by literature and music,” Brooks says.

So is Tyler Herald, executive chef of Patachou Inc., who also keeps bound journals—though his are filled with hand-written song lyrics from concerts he attends. While these pages rarely lead to a specific dish or plating technique, they do help Herald stay creative in the kitchen. Herald also uses his smartphone to snap photos or take notes of things that inspire him culinarily, resulting in a digital food journal he always has with him.

Chef Jonathan Brooks, center.

Chef Jonathan Brooks, center.

PRIMING THE PUMP

Besides capturing ideas as they come, these chefs also have specific processes for conjuring their own inspiration.

For Hardesty, brainstorming sessions are more formal than the loose-leaf sheets might suggest. “It’s definitely something I sit down to do. ‘I need to write menus,’ I’ll say to my wife. And I’ll go in a corner and spread out with a bunch of paper and just start going.”

Brainstorming for Herald is even more formal than that. For Patachou’s two Public Greens locations, for instance, where the menu changes monthly, Herald uses a paper template that begins with the previous month’s menu and, after extensive brainstorming, results in a new menu.

“We’ll take this [handwritten version], which is for our reading, and turn it into a sheet which lists all the things we need, and then eventually that will become the final version of the menu, which is what the guests see,” Herald says.

The process is much different for Brooks, though his approach is just as intentional. For example, Brooks is developing menu items for Beholder based on food memories of employees. The bartenders, servers and other front-of-house staff each drew a number and, one by one, they’ll sit down with Brooks to tell him a favorite food memory.

“I’m going to try to get to the center of what made it special for them, then re-create that here so that they get the chance to talk about something they put on the menu,” Brooks says.

Chef Tyler Herald.

Chef Tyler Herald.

LEAVING A TRACE

While capturing and creating ideas gives life to what chef’s do, what about recording what works? Do chefs leave a trace?

When Hardesty was younger, he kept more of a traditional journal of tips, tricks and techniques, he says, “because things didn’t make sense”

back then. But as he made his way as a chef, “especially in Los Angeles, where I really started to hit my stride, things started to make sense. I can specifically remember the day something sort of clicked, and I got it,” he says.

That was when Hardesty’s journaling transitioned from a “how-to” manual, which he’d often refer to, into his current loose-leaf brainstorming process. Though he can accumulate hundreds of these sheets now, especially when he’s creating menus on a regular basis, he doesn’t keep them for long.

“A lot of it’s just purging onto a piece of paper,” Hardesty says. “Then at least you have it there. That’s when I’ll go back and start scratching things out and reworking them in my head.”

Brooks isn’t much of a recordkeeper, either. Beyond his restaurant- opening journals, which he still has and occasionally refers back to “if I’m stuck or if I’m not feeling inspired,” he didn’t even write down recipes until recently, when his staff encouraged him to do so.

For Herald, however, recordkeeping, and particularly his company’s restaurant-specific food “bibles,” have become critical for Patachou Inc.’s operation.

Each plastic-covered sheet in the three-ring food bibles has the name of a dish, along with a plating photo, description, ingredient list, allergens and serving instructions. These resource books not only guide kitchen staff on cooking techniques and plating; they also help front-of-house staff stay current with changing menus.

“The biggest use of this [food bible], the number one reason, is allergies,” Herald says. “Allergies are huge for our company. Every time someone orders something, the server asks at the end of the discussion, ‘Do you have any allergies that the kitchen needs to be made aware of?’” Also, as Patachou Inc. has opened new restaurants and locations over the years, these food bibles have become important for maintaining consistency and brand integrity.

“Back when we had only one Napolese, it was just me and a sous chef, so there weren’t as many variables,” Herald said. “And it took me until we opened a second Napolese and a third Napolese to realize that everything has to be the same, has to be consistent. It makes all the difference in the world. It’s why this is really important.”

So whether they’re for gathering, brainstorming or storing ideas, chef’s journals don’t come one-size-fits-all. Rather, as Brooks observes, they’re part of “an open food conversation” that he and the others are always having.

“Maybe that’s more what my food journal is,” Brooks says. “It’s a living journal.”