From Dame School to Food Labs

When a visitor entered a typical Indiana junior high school in 1966, chances are they would notice a delicious aroma coming from a far corner of the building. If they followed that scent down the hall and into the room where it was wafting from, the guest might have viewed clusters of aproned teenaged girls in several mini-kitchens. As the noise from spoons clanging against metal mixing bowls mingled with chattering voices, the students likely checked time sheets and consulted purple-ink mimeographed recipes. And there was a high probability that the creation of that home economics food lab would have been a made-from-scratch cake or pie.

Fifty years ago, devising class schedules might have been a little simpler for Indiana seventh and eighth grade guidance counselors than it is today. Every student took math, English, history and their other required courses—and if you were a boy, one of those required classes would have fallen into the industrial arts category while the girls enrolled in home economics.

These days, middle schools and high schools offer a myriad of choices, Foods One is no longer a required course, and the nutrition and wellness courses have been absorbed into the discipline of Family and Consumer Sciences (FCS)—a large umbrella including classes for everyone such as Interior Design, Fashion and Textile, Child Development, Parenting, Consumer Education, Interpersonal Relations and Preparation for College.

Early Beginnings

The roots of home economics began in the East, after the American Revolutionary War, when it became acceptable for girls to attend school. Dame schools, which taught skills needed to maintain a home, were often held in the kitchen of the woman teaching the class, but eventually became part of the public school system. Later, in the 1870s, young women enrolled in both private and public cooking schools that originated in Boston and New York City. At the same time, land grant colleges were being established in the West, and classes such as cookery and household arts were offered to women students.

Another important event that raised awareness in this area of learning was the 1893 World’s Fair. Held in Chicago, it featured an exhibit of the home of a workingman’s family that lived on $500 a year. The woman responsible for that exhibit, Ellen H. Richards, is credited as being the founder of home economics and was the first woman to enter the renowned Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She worked there as an instructor in sanitary chemistry until her death in 1911. Although she never taught home economics, she wrote books on the subject and gave lectures on the importance of establishing it as a field of study. She stressed the importance of using chemistry and science to give the field credibility.

Indiana Jumps In

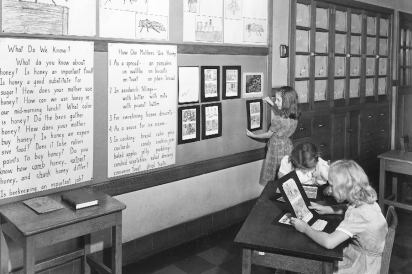

In Indiana, sewing and cooking were introduced to schools in 1894 and a law was passed in 1913 that made them a compulsory subject. A 1915 article from the Indiana Department of Public Instruction titled “Outline of Work in Domestic Science” set out the curriculum for a two-year course. Subtopics included were Dirt and Its Dangers and Duties of a Hostess and Use of Left-overs. Most of the time, culinary techniques were taught by the observation method: Students gathered around while the instructor demonstrated. When there was an actual hands-on cooking lab, it consisted of gas burners arranged around the teacher so she could observe what everyone was doing at the same time.

After being almost eliminated during the Depression, home economics became a strong force in the 40s. During the time of rationing and scarcity brought on by World War II, students were taught how to maintain proper nutrition and sew affordable clothing. Technology had advanced and instructors used films and slides. The lab portion of instruction evolved to teams of girls working in their own kitchen space. Most schools had electric refrigerators although in the early years of the decade, a wooden box cooled by a block of ice was used.

Boys Join the Fun

Starting in the late 60s and continuing to the 70s, some Indiana schools offered courses open only to boys. Cindy Eiteljorg, who taught in Wayne Township, Indianapolis, instructed a class called Bachelor Living. Eiteljorg remembers, “Students sewed chef hats, which they then wore during food labs. Enrollment was always filled to capacity.”

Barb Diehl, a teacher in the Fort Wayne Community Schools during the same era, said, “Most boys still took shop, which was often located close to the Food Lab. When the girls cooked something that did not turn out well, they would take it over and it would be eaten up in no time!”

New Name Brings Changes

In 1995, Indiana followed the national trend and adopted the name Family and Consumer Sciences for its home economics programs.

“The field had evolved from a focus on homemaking skills to more scientific and research orientation; social and economic issues facing families and shift to career preparation were better reflected by the change in name,” said Alyson McIntyre-Reiger, FCS program leader for the Indiana Department of Education. “In the 1900s Ellen Richards used her microbiology degree from MIT to solve safe drinking water for families and FCS continues to assist in creating healthy and sustainable communities.”

Currently, a dedicated team of secondary teachers covers the FCS classes for Hamilton Southeastern Schools. Amy Asher, Lee Ann Self, Elizabeth Trinkle and Cynthia Ziemba range in experience from two years to 34. Self travels between schools, but the classes offered at each site vary due to student demand.

FCS courses seek to give students practical knowledge as well as prepare them for a possible career. Trinkle, whose Fashion and Textiles class cumulates in a Royal Project Runway Style Show that benefits Riley Hospital for Children, said, “Today, FCS has something for everyone.”

Asher stressed, “Basics are still being taught, but with today’s technology.”

Ziemba, who teaches the popular class Senior Foods, said, “My goal is to teach students that they can cook for themselves both to save money and eat healthier. FCS, in general, teaches life skills that will help them personally and professionally.”