Finding New Directions

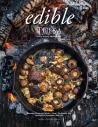

Students at the Felege Hiwot Center picked apples and made pies. photography: courtesy Felege Hiywot Center

Felege Hiywot Center grows both crops and character. Felege hiywot means “looking for direction to life” in Ge’ez, an ancient Ethiopian Semitic language. FHC helps junior and senior high students find exactly that in its RISE initiative, an employment- and agriculturebased STEAM (science, technology, engineering, art, math) program.

Students are encouraged to apply lessons learned from urban farming and community service into strategies to meet all of life’s challenges. Although FHC had a humble beginning, it is now a strong force not only in preparing individuals for the future but also in building a sense of place.

Nestled in Martindale-Brightwood, FHC serves an ever-changing population of youth. In the 1870s the historic near-northeast Indianapolis locale was two distinct areas: Martindale was home to segregated African Americans and Brightwood was inhabited with first-generation German and Irish railroad workers. Today the population is mostly African American along with a slight Latino and Caucasian representation.

“In Ethiopia, elders are our library. They may tell the same story over and over, but each time we hear it, we learn something new.” —Aster Bekele, Felege Hiywot Center founder

As a young college student living in the neighborhood in the 1970s, Aster Bekele was grateful for the opportunities she had before her, but never lost sight of the culture she left when she emigrated from Ethiopia.

“In Ethiopia, elders are our library,” she says. “They may tell the same story over and over, but each time we hear it, we learn something new.” While heeding her inward call to contribute to the community by tutoring some of the area schoolchildren, she had a dual realization: working with youth and connecting with elders goes hand in hand. Those two concepts formed the focus when she founded FHC.

“I want to build on the rich history of the Martindale- Brightwood elders I met and keep it alive by engaging the students we serve by asking them to interview their grandparents or any elders they know in their community.”

Over the years, the programming offered has been flexible to meet the needs of the area’s changing demographics while remaining true to the traditions of values on which it was founded. Initially a boarded-up property on which two rundown houses sat, the center now supports multiple outdoor garden plots, a small greenhouse and a polytunnel greenhouse.

In 2021, FHC was awarded a $2 million grant to be disbursed over five years from Lilly Endowment, Inc., through its initiative Enhancing Opportunity Indianapolis. The grant supports RISE, an acronym for the mission of the program: Resilience and drive; Inquiry and ingenuity; Social impact; and Economic security.

“We don’t assume that students come to us already knowing how to do things,” says Bekele. “We meet them where they are. We mix the teams with three groups: those that have leadership experience, those in the middle and those that don’t have that experience yet. The students follow the scientific method to find answers to their inquiry. When using the scientific method, they may have to circle back to step one, but nothing is considered a mistake—only learning.

“Job requirements at FHC are unique,” she continues. “We want their innovation ideas on how to accomplish a task. So engaging their minds and teamwork is required. One example from summer camp 2022 was, after training on time management and teamwork, we gave them a task to figure out how to fill 60 raised beds with 27 cubic yards of blended soil. They had three days to finish. They had an option to use our detailed instruction or come up with their own. They decided to put their heads together and come up with a plan.

“On the first day of the plan, they managed to fill six beds and some half beds. At the end of the day, we took them through a calculation of the time it took them to fill the beds and, based on that, they would need 16 hours more to do the rest of the beds, which meant they wouldn’t meet their goal. They regrouped and talked on how to put each student on the task they were properly fitted with. On the second day they did 10 beds, which means still they wouldn’t be ready to plant by the fourth day. They did more discussion on improvement and on the third day they did 44 beds, accomplishing their goal.

“FHC jobs require mind engagement. As scientists we are getting paid to discover new ways of doing things and we want students to experience that,” says Bekele. In their horticulture investigations, students follow another acronym. The word PLANTS is used to teach the basic needs of all the center grows. All growing things require Place, Light, Air, Nutrients, Thirst (water) and Soil.

“Students each get an individual planting bed. Nothing is a failure; it’s all a learning experience,” says Hope Staton, farm instructor/manager. “The garden zones are taught along with what grows in our climate at the time. Information is given on what can be done to push it such as the polytunnel or ground cover. Students develop a plan, chart a time frame of what they expect to happen and why.”

The students follow the scientific method to find answers to their inquiry. When using the scientific method, they may have to circle back to step one, but nothing is considered a mistake—only learning.

(left)FHC students tend the beds inside their tunnel greenhouse; (upper right)Apple pie making in the FHC kitchen; (lower right)Through a partnership with Purdue University’s Botany and Plant Pathology department, FHC students learn to identify plant parts and describe them through drawing.

”I’m never going to say no to students’ desire to grow vegetables we haven’t grown before,” Staton says with a chuckle. “I’ve spent hours searching out dwarf lemon seeds on Etsy. I’m also looking for tangerine and dragon fruit. It will be an interesting experiment.” Staton, who is originally from Virginia and working towards her master’s in divinity degree, came to Indiana to attend Bethany Theological Seminary, located in Northwest Indiana. Before that, she was in the Brethren Volunteer Service.

“I came because I had a calling to the ministry, but not necessarily as a pastor. I became involved with FHC to teach Junior Master Gardening plus health and nutrition. When I was asked to take the position of farm instructor/manager, I couldn’t pass it up,” says Staton. “People think teenagers aren’t interested in farming, but that’s not true. Give them the opportunity to have space and not label anything as a failure, they will jump through hurdles.”

When the students are not gardening, a portion of the day is devoted to teaching core skills such as positive mind-sets, work ethic and learning strategies as well as social and emotional skills. The skill sets taught involve resume writing, interview coaching and entrepreneurial concepts. Students are encouraged to plug everything, even disappointments and relationship development, into the scientific method.

In their horticulture investigations, students follow another acronym. The word PLANTS is used to teach the basic needs of all the center grows. All growing things require Place, Light, Air, Nutrients, Thirst (water) and Soil.

“It is lovely to have families here. When we have events that include them, Ms. Aster makes wonderful Ethiopian food. She spends a whole week cooking it,” says Staton. It is always a feast of stewed meats, lentils and vegetables fragrant with spices and served with injera, Ethiopia’s staple fermented teff bread.

FHC relies on volunteers. They are always needed, and Bekele refers to them as “our lifeline.” There is plenty of work to be done from maintenance of the facility to farm weeding. Unfortunately, during COVID volunteer program dropped to zero and the farmers market ceased operations. Both are currently being brought back to life.

The application process for FHC’s summer camp begins in early spring and the program begins the second week in June. Information is posted online at AfterSchoolHQ.com and word of mouth is spread by already-participating families. Most students return year after year; alumni stay connected and return to do university research.

“Past graduates come in the last day of camp to tell their story,” says Bekele.

“Students can see how far they have come. The key is persistence and not giving up. Whatever the struggle is, they learn to hold on and always connect to their roots.

“It is a gift to guide somebody,” she continues. “It doesn’t matter where you go; you are always carrying someone’s hand with you to push you forward. It is alright to leave and love a new place, but never disconnect from where you came from.”

Felege Hiywot Center

1648 Sheldon St., Indianapolis

FHCenter.org