The History of Pork Packing in Indiana - How Little Piggies Go to Market

When I was a young girl, late fall weekends often meant accompanying my parents to a friend’s farm to help butcher hogs. Of course, I often stayed inside and played with the cats during the dirtiest work, but once they got to the lard rendering I’d make an appearance. Fresh cracklins were hard to resist.

Small-scale pork processing and packing, like my parent’s friends did, was almost unheard of in the 1970s and 1980s when I was a girl; several cultural, economic and technological advances coincided at the end of the 19th century to bring an end to small-scale pork processing. However, a century earlier when Hoosiers were far more self-reliant for their food supply, the practice was much more common.

“In the opening decades of the 1800s innumerable farmer-packers either killed animals and cured meat for their own use during the winter months or took their surpluses in the form of ‘dead’ meat or livestock to local market towns on the Ohio-Mississippi River system,” writes Margaret Walsh in her book The Rise of the Midwestern Meat Packing Industry.

But population growth in large northeastern and Midwestern cities portended a new way.

“By 1870, 40.3 percent of the population of the Northeast and 20.8 percent of the population of the Midwest were urbanized. Assuming that all of the 8.1 million city residents in these two regions ate 122 pounds of pork per year and that western packers supplied 70 percent of their requirements, then domestic demand far outstripped supply,” Walsh writes. “Furthermore, the foreign market was expanding, and by 1870, 11.5 percent of western-produced bacon, ham, and barreled pork was exported. Most assuredly packers could sell their increasing meat outputs.”

Besides urbanization and increased demand for factory-processed food, the pork packing industry also grew through the expansion of railroad lines and the development of faster communication through newspapers and the telegraph. As well, innovations inside the packing industry fostered efficiency and consolidation. According to Walsh, improved business structure and the implementation of ice packing during the summer months allowed some packing companies to grow exponentially.

“Not all midwestern packers adopted these improvements,” Walsh writes, “but among those who did were the leading firms who came to control a large share of the regional product.”

As well, new professional organizations were developed that led to more standardized guidelines for meat packers’ business conduct. This in turn created a “type of general efficiency” that made it “increasingly difficult to thrive as an independent small-scale pork merchant in an industry that was becoming more systematically organized.”

Walsh named two Indiana packers who failed to adapt to the rapidly developing packing industry. Wabash River merchants Jacob D. Early in Terre Haute, and Henry T. Sample in Lafayette, were long-time residents and traders who provided pork packing in addition to other commercial and financial interests.

“This partial and intermittent commitment, like commission work, may have been the way forward in the pioneer years of the meat industry,” Walsh concluded, “but in the late 1860s both practices were indicative of the decline of rural participation in agricultural processing.”

Hammer Family of Spiceland

Another Hoosier swept up in the swift transitions of the late 19th and early 20th century was Willis S. Hammer in Henry County’s Spiceland Township, about 40 miles east of Indianapolis. Hammer operated a slaughterhouse for many years. While not much is known about Hammer or his family, a photo taken in the late fall of 1898 shows Hammer with his wife, Josie, and daughter Lela May standing among hog carcasses, with a cutting table in the background and kettles for lard rendering in the front.

His obituary in 1916 says he was a carpenter and a contractor, which seems to indicate that like Early and Sample he was a meat packer on the side. The photo shows an entirely outdoor operation, dependent on the weather for success. And Spiceland remains to this day a rural area, with no access by train. For small, part-time packing operations like the Hammer Family, the tides of changes swept them into the past.

Kingan buyer L.M. Maroney with John Hardin and his Grand Champion Barrow at the 1935 Indiana State Fair. Photo courtesy of Indiana Historical Society, P0490.

Kingan buyer L.M. Maroney with John Hardin and his Grand Champion Barrow at the 1935 Indiana State Fair. Photo courtesy of Indiana Historical Society, P0490.

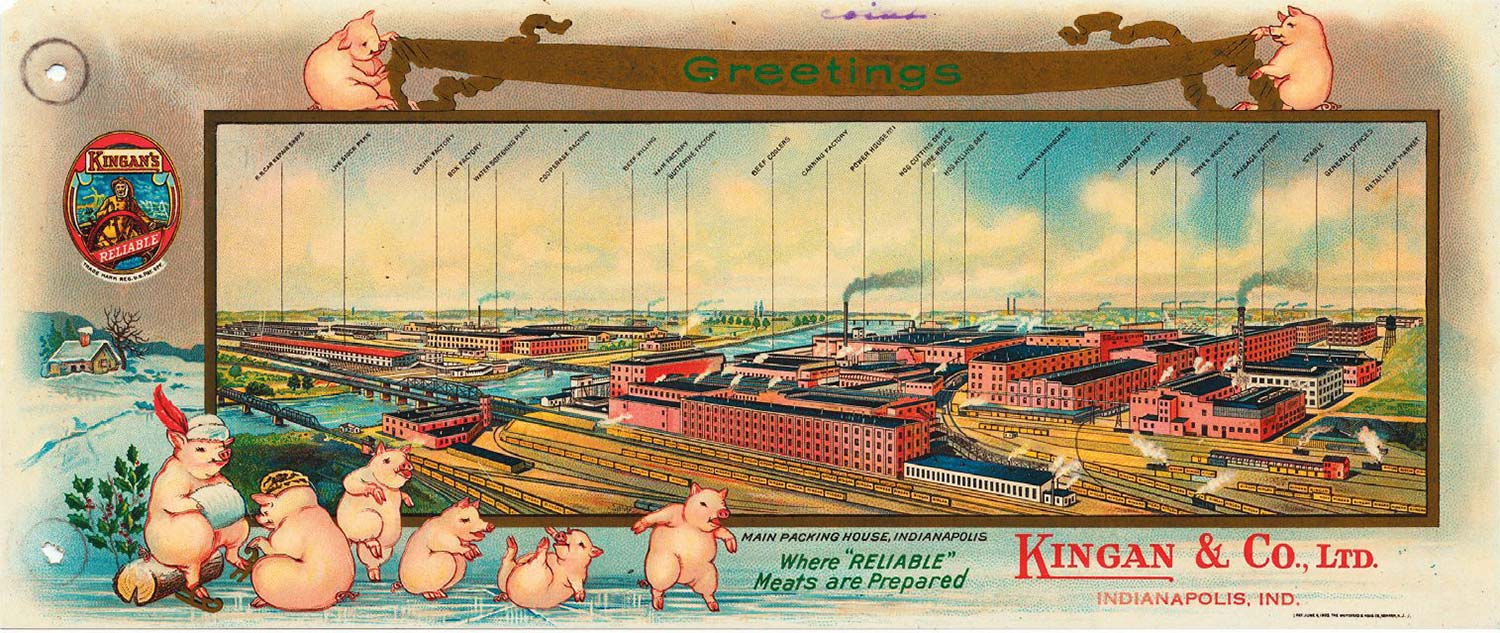

Kingan & Co.

On the other hand, two Irish immigrant brothers who made their way to Indiana from Brooklyn then Cincinnati deftly navigated the increasingly urbanized and industrialized processes of the Reconstruction era in America.

Having opened meatpacking operations in both of their previous cities only to watch them burn to the ground, literally, Thomas and Samuel Kingan arrived in Indianapolis ready to try again. They built a five-story facility on the west side of Indianapolis near the White River and began operations in 1863. Unfortunately, like their previous two facilities, the Indianapolis plant also burned to the ground. Investigators believed the blaze was the work of arsonists. The Kingans had learned from their previous experience, though, and had insured their third plant. They turned their $240,000 loss into a new facility and quickly reopened.

Wartime sales to the Union Army and exports to Great Britain helped Kingan prosper. In 1868, George Stockman, a Kingan employee, invented an ice-curing process that allowed their pork packing to continue year-round. They purchased a competing pork-packing plant across the railroad tracks in 1873, and then in 1875 they merged with Belfast firm J&T Sinclair to form Kingan & Co., one of the largest meat-packing operations in the world. In 1887, Kingan built several ice houses along the White River in Broad Ripple, just north of downtown Indianapolis. Ice was harvested from the river and stored until summer, when it was shipped down to their downtown packing plant.

When Thomas Kingan died in 1906, his business partner W.R. Sinclair came to the U.S. to manage the business. Five years later, Samuel Kingan also died, and another Sinclair family member, Thomas, moved up the ranks in the company. The Sinclair family ran the business until 1952 when Detroit-based Hygrade Corp. bought Kingan & Co. Under Hygrade, the company lasted until 1966 and then closed permanently. A year later, the Hygrade plant burned to the ground.

Pearl Packing Co.

About the same time the Kingans were investing in their ice house, Augustus Yunker of Madison was opening up his family’s own packing plant and ice house along the Ohio River. The Pearl Packing Plant opened in 1890 and grew steadily over the years. In 1917, Pearl Packing was incorporated, earning annual revenue of about $200,000.

Pearl Packing manufactured sausage and lard, but also processed other kinds of meat. They also had an ice-packing business. Their products were distributed throughout the Midwest, especially to Louisville, Cincinnati and Indianapolis, and eventually throughout the country.

Over time, Augustus Yunker’s four children—Georgine, Marie, Robert and Leo—became involved in the business until it closed in 1972.

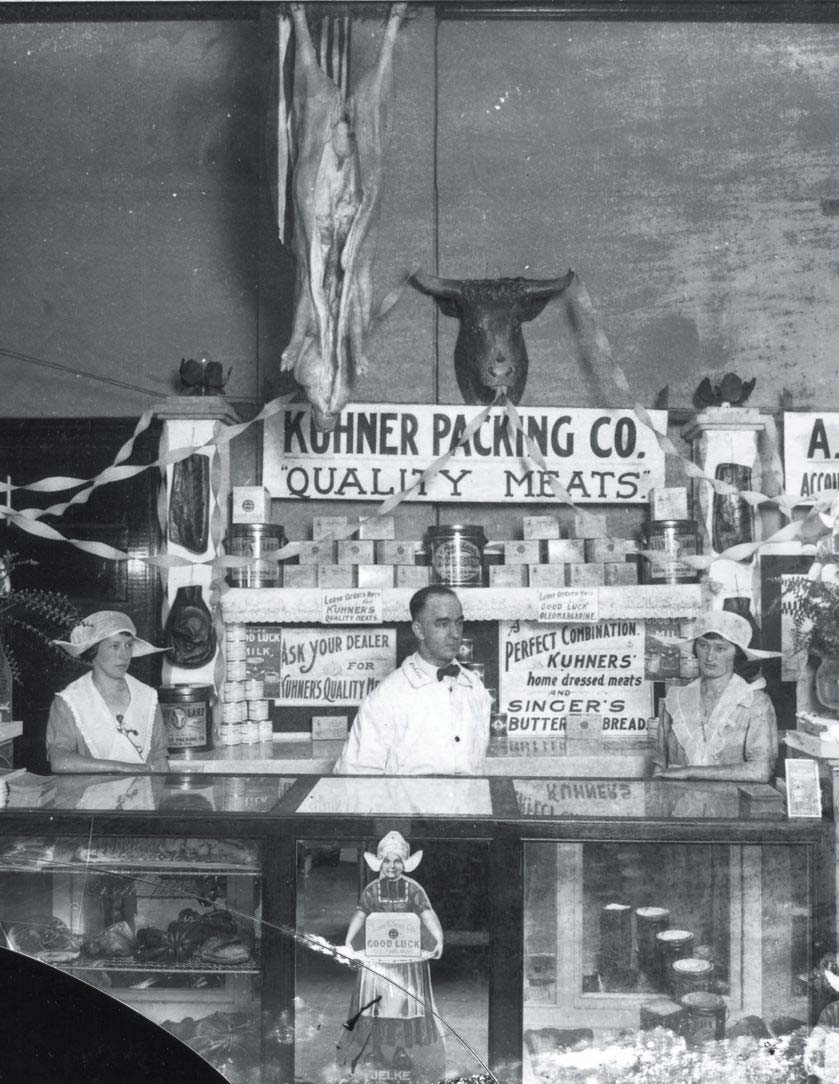

Kuhner Packing Co., Muncie, 1922. Photo courtesy of Ball State University Libraries.

Kuhner Packing Co., Muncie, 1922. Photo courtesy of Ball State University Libraries.

What commercial meat curing looked like in 1936. Photo courtesy of Martin Collection, Indiana Historical Society.

What commercial meat curing looked like in 1936. Photo courtesy of Martin Collection, Indiana Historical Society.

Kuhner Packing Co./Marhoefer Packing Co.

Meanwhile, in the North Central part of the state, Gottlieb Kuhner and his sons established the Kuhner Packing Co. in Muncie in 1901. By 1911, the Kuhners incorporated to become Kuhner and Co., and by 1913 their business included nine retail butcher shops in addition to the Kuhner Packing Co.

In their packing division, the Kuhners produced bacon, sausage, dried beef, ham, lard and other products. Over the years, Kuhners also became known for their hot dogs. A 1929 advertising campaign claimed “Kuhner Meats Make Keener Appetites.”

In 1945, Kuhner Packing Co. was acquired by the Marhoefer family and became known as The Marhoefer Division of Kuhner Packing Co. After a 1952 merger with other Marhoefer interests, the Kuhner name was dropped and the business became known as the Marhoefer Packing Co.

As the pork production industry became less profitable in the 1970s and the Marhoefers lost their lending arrangements, they were forced to file bankruptcy and the company dissolved in 1978. In the same year, long-time Marhoefer employee Jerry Jones became president of the Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butchers Local P-105 Union.

Hoosier women were critical in all fi elds of work. This post-World War II image shows women working alongside men in a Home Packing Co. dressing room, 1950. Photo courtesy of Martin Collection, Indiana Historical Society.

Hoosier women were critical in all fi elds of work. This post-World War II image shows women working alongside men in a Home Packing Co. dressing room, 1950. Photo courtesy of Martin Collection, Indiana Historical Society.

Home Packing Co.

A few years after the Kuhners got their start, the Home Packing Co. was founded in Terre Haute in 1907. Over its years of operation, Home Packing processed anywhere from 350 hogs a week to more than 10,000 hogs per week during its peak operation. It was well-known for its Dependable brand of bacon, hams, bologna and lard. Products were shipped all over the world from the Terre Haute plant.

Unfortunately, Home Packing became most known for a 1963 gas explosion that killed 17 employees and injured 50 more. The plant never reopened after that incident.

1905 Kingan & Co. greeting card. Photo courtesy of Indiana Historical Society, P0411.

1905 Kingan & Co. greeting card. Photo courtesy of Indiana Historical Society, P0411.

Dewig Brothers Packing Co.

In 1916 John Dewig and his two brothers, Anton and Joe, formed Dewig Brothers Packing in their southern Indiana town of Haubstadt, just north of Evansville. Beginning their processing and packing operation with no equipment other than knives, they entered the meat industry following in the footsteps of their father, who was a butcher.

The Dewigs’ business endured the Great Depression of the 1930s and, like the Kingans, also survived a devastating fire in 1937. Within a year, the Dewigs had reconstructed the plant and resumed operations. In 1962, John Dewig’s sons, Tom and Bill, purchased the packing business, and another fire in 1967 forced them to rebuild again.

The Dewig Brothers Packing Co. has weathered many other struggles over the years, particularly supply and demand pressures and high-tech, large-volume competitors, but they have remained one of the longest-running family packing businesses still operating in the state. They continue their commitment to high-quality products and personalized service for their customers, not only in their meatpacking and sausage operations, but also in their online retail and catering businesses, which can be found at DewigMeats.com. They also are well-known by customers for their barbecue products and their authentic German bratwurst.

Pork packing in Indiana has come a long way from the part-time pioneers who dressed hogs in the winter months and sold the extra at market. But the families and employees of the packers who are in business today still seek to feed their fellow Hoosiers with their dedicated service and quality products.

Dewig Brothers Packing Co.’s fi rst meat market, Haubstadt, 1916. Photo courtesy of Dewig Meats.

Dewig Brothers Packing Co.’s fi rst meat market, Haubstadt, 1916. Photo courtesy of Dewig Meats.

The Food and Drug Act

Just before the Dewigs got their start and about the time Home Packing was founded in 1907, Upton Sinclair’s Th e Jungle was published, permanently changing the landscape of meat production and packhouse working conditions. Th at same year, Congress passed the Food and Drug Act, which established the food inspection process and made it a crime to sell adulterated food. By 1922, Th e Packers’ Encyclopedia was published by Th e National Provisioner. Th e guide book included sections on best practices for hog killing, cutting, curing, ham boning and cooking, lard manufacturing and preparing pigs’ feet. It also contained sample diagrams of a killing fl oor, a smokehouse operation and a lard refi nery.

OTHER INDIANA PACKING COMPANIES

Today, Indiana is home to several other packing plants, most started after World War II and in the decades that followed.

MISHLER MEATS

LaGrange - MishlersMeats.com

MANLEY MEATS

Decatur- ManleyMeats.com

INDIANA PACKERS CORPORATION

Delphi- IndianaPackersCorp.com

HANFORD PACKING COMPANY

Thayer - HanfordPackingCo.com