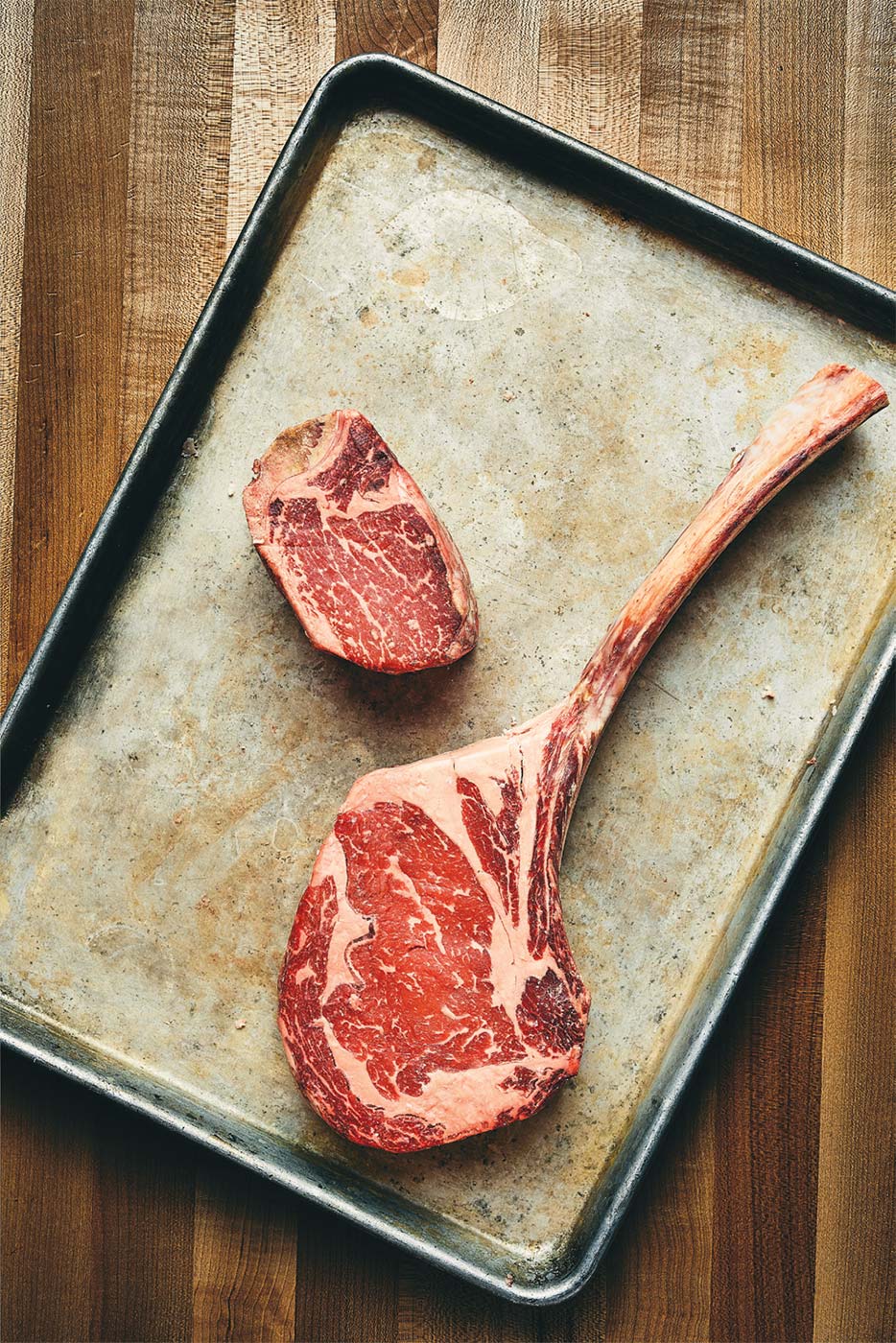

IT’S IN THE BEEF: Indiana-bred Black Angus

Indiana-bred Black Angus is served at some of the country's best steakhouses

Raising what some consider the best beef in the world isn’t something that happens overnight. It’s a well-thought-out process that, like other great ventures, takes time, patience and dedication.

“It all starts from the beginning,” says Fred Linz, of Linz Heritage Angus, about raising superior beef. First, he says, you start with the best beef cattle in the world. Then you use genetics and proper breeding techniques to continually produce an exceptional product. Family-owned and -operated since 1963, the Linz family has been farming Angus cattle for more than 55 years.

“We breed Black Angus cattle with the finest genetics in the world,” Linz says, adding that it’s their mission to continue doing so in a manner that produces some of the most consistently marbled Angus available. And it’s their dedication to superior quality that’s helped place their product in some of the nation’s top steakhouses.

“Black Angus is the premium breed for steakhouse-quality beef,” says Chris Clifford, vice president of business development and purchasing for Huse Culinary—the group that owns St. Elmo, Harry & Izzy’s, Burger Study and the soon-to-open HC Tavern and Kitchen.

“We were looking to partner with a meat supplier that could provide us with 100 percent genetically verified Black Angus,” says Clifford of the group’s decision to partner with Linz Heritage Angus. Additionally, the group wanted their beef sourced from one processing facility in the Midwest, and Linz met those needs. Originally operating out of Calumet City, Illinois, Linz still has a presence there but now also runs two Indiana cattle farms—in Crown Point and Cedar Lake.

“We look to source the best,” says Craig Huse, co-owner of Huse Culinary. “If the best or equivalent is local, then we establish that local relationship.”

Along with Linz, the group works with many locally based organizations including Viking Farms, Hubbard & Cravens, Smoking Goose, Caprini Farms and Fischer Farms. And it’s these relationships that help St. Elmo Steak House create the dishes that keep patrons coming back, year after year.

THE GOLD STANDARD

St. Elmo is the longest-standing steakhouse in Indianapolis, serving out of its original location since 1902. And though it’s known for serving a wicked-hot shrimp cocktail and unmatched, professional service, it’s the steak that locals and out-of-town guest rave about. “We serve everything from a 60-day-dry-aged USDA prime tomahawk ribeye, to a 30-day-wet-aged USDA prime NY strip, to a properly trimmed, 30-day-aged center-cut USDA choice filet, to a grass-fed flat-iron steak,” says Huse of their menu selections, adding that ultimately it’s their guests’ preferences for flavor, tenderness, feed style and even price that drives their menus.

“It’s our responsibility,” says Huse, “to identify our patrons’ priorities then exceed their expectations.” And it’s this responsibility and commitment to serving excellent steak that Clifford says brought the Huse group to buy an Angus bull and work directly with Linz to develop a genetic program for raising cattle that provides an unprecedented quality of beef to their guests.

GRADE, AGE, FLAVOR

Angus is a particular breed of beef cattle, while prime, choice and select are the three most commonly seen of the USDA’s eight beef grades. Though there are other criteria, the main determinant for grading beef is the amount of marbling, prime having the highest levels. Only 2 percent of all beef in the U.S. is labeled prime, with around 45 percent graded choice and 21 percent, select. Typically, Angus has a higher concentration of intramuscular fat, making a USDA prime-grade Angus steak one of the most flavorful cuts of beef in the world—and when it’s dryaged, the flavor becomes even more intense.

Different than wet-aging, which means meat has been allowed to age inside a vacuum-sealed container, dry-aged beef is hung in a temperature-controlled room regulated for airflow and humidity levels. Wet-aging beef takes less time and costs the manufacturer less to produce, typically resulting in a lower market price than dry-aged beef. But the real difference is in the taste and texture, which many steak enthusiasts agree is tender, rich and buttery with a slight earthy flavor.

“Dry-aging beef removes a significant amount of moisture from it,” says Michael Christensen, Huse Culinary director of culinary. This “concentrates and enhances the flavors.”

The distinct flavor profile of a Linz Heritage Angus dry-aged steak has an almost woodsy aroma that reminds Linz of mushroom picking with his grandfather—and it’s this unique characteristic that’s earned it a place at the table in many high-end steakhouses in the U.S. including St. Elmo, the famed Manny’s Steakhouse in Minneapolis, Ditka’s and others.

As for the process of dry-aging beef, interestingly enough, one of Clifford’s favorite wines is made in a similar fashion.

“I have been a big fan of the Italian wine Amarone della Valpolicella for almost 30 years,” says Clifford of this rich, dry red—his all-time favorite wine to have with steak. Amarone is made from grapes partially dried in a controlled environment, similar to the way beef is dry-aged.

Once harvested, the ripe grapes are placed on mats where they dry and shrivel for upwards of 120 days, which concentrates and intensifies flavor. There are, Clifford says, many parallels in the dry-ageing of grapes and beef. Everything from the growing and nurturing, to the varietal choice or breed choice … ultimately, all affecting the final product—be it a wine or a steak. Linz agrees.

“Grapes,” he says, “grown in different regions have different flavor profiles, and cattle is no different.” Want to learn more about the process of raising Angus beef with the finest genetics in the world? Be sure to watch for our Fall issue, where we’ll dive deeper into the methods used to raise 100 percent black-hide Angus.

WANT TO COOK A DRY-AGED STEAK AT HOME?

Here are five tips from Michael Christensen of Huse Culinary to help you:

- Cook dry-aged cuts to no more than medium-rare to keep them from becoming too dry.

- Don’t over-season as sodium pulls remaining moisture out.

- If you season, do so lightly and do it right before cooking.

- Let beef come to room temperature before cooking.

- Sear on a “rocket-hot” broiler to help seal in remaining moisture, then reduce heat to finish.

photograph courtesy: Linz Heritage Angus

photograph courtesy: Linz Heritage Angus

To be classified as Angus, by law the beef must come from cattle that has Angus influence and is at least 51 percent black—Linz Heritage. Angus, served at St. Elmo and a few other upscale steakhouses, is 100 percent blackhide, Angus beef.

THE ANGUS DIFFERENCE

A lot of firsts happened in the 1870s. The decade opened with John D. Rockefeller founding one of the world’s first multinational companies, Standard Oil Company, and soon after, the state of Mississippi elected the first African American to congress. Two years later, President Ulysses S. Grant declared Yellowstone the first National Park, and by the end of 1875, the first zoo on American soil would open in Philadelphia. And during this time, in the small British settlement of Victoria, Kansas, Scottish-born George Grant was procuring greatness with the development of what many consider the best beef in the world—American-born and -bred Black Angus.

With a dream to build an English ranching colony, Grant had four Aberdeen Angus cattle imported from his homeland. Sadly, the settlement would be devastated by drought, prairie fires and grasshoppers and many settlers, unequipped for the harsh environment, perished. Impervious to what some saw as failure, Grant stayed on and with help from others who shared his dream eventually was able to breed the hardy, Scottish-born bulls with native longhorns—producing extraordinarily black, hornless calves. The crossbreed thrived and though initially thought of as freaks, because they had no horns, they proved better able to survive winters, on average weighing 150 pounds more come spring. Thus, the demand for this type of cattle grew and between 1878 and 1883, roughly 1,200 cattle were imported, most of them to the Midwest. Nowadays, there are registered Angus ranches in all 50 states, and right here in Indiana the Linz family is raising the purest Angus of them all—Angus that’s served in some of the country’s best steakhouses.