Noshes for a New Year: High Holidays Eats

Fall is just around the corner. That means that in a few weeks, if you drop by my house, you’re liable to find me in the kitchen with my daughters. We’ll be chopping up apples and stirring them into a mass of honey and sugar lightened with a little lemon juice, heating water in the canning pot, sterilizing jars and getting ready to can our annual batch of apple-honey jam.

The jam is a sticky and delicious treat that’s worth eating any time, but the girls and I always make it to give to teachers and family friends to say Shanah Tovah (Happy New Year) during Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year. Rosh Hashanah is the first of the Jewish High Holidays, and its combination of celebration and spiritual reflection is a highlight of the religious year. Apple-honey jam is a perfect gift to mark the holiday because Jews have dipped apples into honey for centuries in order to wish one another a Shanah Tovah umetukah—a good and sweet New Year.

That wish informs a lot of the cooking and eating we do during Rosh Hashanah. Sliced apples dipped into honey are the simplest variation. The jam I make is just a more portable version of that. Honey cakes of every variety are a popular treat—whether ordered in from fancy bakeries or made at home from a recipe Grandma handed down. My own great-grandmother made taiglach for Rosh Hashanah. These little knots of dough are boiled in a honey syrup until golden brown and then rolled in nuts. They guarantee sticky fingers as well as a sweet year!

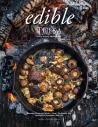

Honey is everywhere during the holiday. It sweetens tzimmes, a glazed carrot and raisin side dish. And honey-roasted chicken is an increasingly popular choice as the centerpiece of dinner on Rosh Hashanah. If you still haven’t had enough sweetness, you can always smear honey on a big slice of challah—the traditional braided bread eaten on Friday nights for Shabbat (the Sabbath).

During Rosh Hashanah, though, that challah looks a little different. Instead of forming one long braid, during Rosh Hashanah challah is formed into a round braid. The circular shape symbolizes the renewing cycle of the year. The fact that a circle ends by returning to its beginning is also a reminder that the end of an old year is a chance to return to the good intentions with which we began it, no matter how far we may have drifted from them.

Some families make a practice of celebrating the New Year with foods that are jokes and puns. Because Rosh Hashanah literally translates as “the head of the year,” fish heads are a feature of some celebrations. Other foods, like beets or dates and gourds like pumpkin or squash, are sometimes eaten because the Hebrew words for them sound like the words for “to tear,” “to consume” and “to remove,” which is what we hope will happen to our sins and to evil-doers. The Yiddish word for “carrot” sounds a lot like the Yiddish word for “increase,” and the carrots that go into tzimmes are sliced into rounds so they look like coins. So those simple carrots can be seen as a wish for a New Year filled with prosperity.

Ten days after Rosh Hashanah comes the most solemn holiday in the Jewish Calendar: Yom Kippur, the day of repentance. When it arrives, Jews fast from sundown on one day to sundown on the next day—eating no food and drinking no water during that time, and spending as much time as possible in prayer, contemplation and study. Knowing that, it might seem funny to talk about traditional foods for Yom Kippur. (I like to joke that my recipe for dinner on Yom Kippur is “air and prayer.”) But after you have fasted for a full day, you’re ready to eat!

That means what matters most for the “break the fast” meal after Yom Kippur is that there’s good food, plenty of it, and that you can get it on the table quickly. My friend Rachel relies on bagels and lots of spreads. She doesn’t like to cook during the fast since she wouldn’t be allowed to taste anything. I feel the same way, so I make a coffee- and spice-rubbed brisket that needs to marinate in its sauce for 24 hours after cooking. I take it out of the oven before the fast begins—put it in the fridge and ignore it while I’m fasting—and quickly reheat it once the sun goes down. My friend Leah’s food traditions are Sephardic—from the Jews of Morocco, Spain, Portugal and North Africa. Her family loves hot pepper salad and borekas, which are savory pastries stuffed with a wide range of fillings, for their break the fast.

Other families will rely on kugel (a baked noodle pudding with infinite sweet and savory variations), strata or other familiar brunch food. My fiancé doesn’t feel like he’s really broken his fast until he has a good garlic dill pickle, and some friends of his always start their meal with a fast shot of slivovitz—a highly alcoholic plum brandy. Less adventurous souls will ease out of their fast with a cup of tea and a slice of challah or plain cake before they move on to more serious eating.

The High Holidays of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur are the backbone of the Jewish year. And the foods we eat during those holidays help us to celebrate together, to restore us after a day of atonement and prayer, and to symbolize our hopes and our wishes. So have a little something sweet on the evening of October 2, when Rosh Hashanah begins, and maybe grab a bagel for dinner on October 12, when Yom Kippur ends. And may your New Year be filled with sweetness and new recipes.