From Tibetan Refugee to Hoosier

Pema Wangchen is far from the typical Hoosier.

He wears a small diamond stud earring in his left ear, a metal om symbol around his neck hanging on a colorful string, a black bracelet on his right wrist that says Paris and a rainbow-colored one on his other that says “H.H. Dalai Lama.” He sports a mini-goatee under his chin with a smaller patch of hair under his lip to match. It’s hard to believe he’s in his late 30s, with his black hair slightly long and spikey on top and his childish grin. But there’s a few grays here and there showing that this Tibetan refugee—once a Buddhist monk and now a chef and owner of the restaurant Anyetsang’s in Bloomington—has lived.

“I lived in Tibet 12 and a half years,” he said, recounting the remarkable journey that brought him here. “The Chinese took over Tibet in 1959 … poor, no school, no anything, so my parents work hard and they save some money. They sent me to India.”

When he was young enough to still count his age by half-years, Pema’s parents stitched a few hundred dollars into his clothes and sent him on a three-day bus ride from his hometown of Shingtsang Noe to Lhasa, Tibet’s capital, so he could find a better life. He would stay with one of his father’s relatives for a few days before he paid $75 to take a long, packed truck ride into the darkness, along with 50 other Tibetans, to the northern edge of Nepal. And then, their long journey officially began.

“Then we walk … walk … walk … we climbed the mountain.” He raised his right hand at a 45 degree angle to show how steep the mountain was, then sipped on his chai.

“We climbed mountains that were like sand. You walk, fall down. Walk, fall down. Seven or eight hours we hiked and so heavy my food. I just threw it away … I said ‘I can’t make it, it’s so heavy.’”

It was at this point Pema found himself at the bottom of a mountain people train for years to summit—Mt. Everest. They hiked at its foothills in the night.

After abandoning his food, he ate mostly tsampa, which is a Tibetan staple comprised of barley flour and used to make bread. Light-heartedly he tried to explain what it was to my friend Kim and me. He then got up and walked to his restaurant’s kitchen. Anyetsang’s is in an old house hidden by low trees on Indiana University’s campus in Bloomington along a street of other Asian food spots. He came back with a bag of what looked like dark-colored flour for us to inspect.

“It’s yummy,” he said, grinning and sitting back down to twist the Dalai Lama’s name around on his wrist for a minute. Then he continued his story.

“Mountain, ice, rocks … so dangerous.” Pema let out a sigh and squinted his already narrow eyes a bit as if he was back in that moment long ago.

And finally, they reached the Himalayas, a place Pema says is sacred and there was often prayer in this area under the hanging flags above them. He was too young to understand the significance then, but understands it now. There, he ran out of food altogether and had to dig into the stash sewn into his clothes to buy goods, like potatoes, from the Nepalese locals.

They walked more. It was cold and snowy. An old woman died along the way; a few people were sent back because it was simply too treacherous for them. And 33 days later, they arrived just outside Kathmandu, Nepal’s capital. There they boarded a bus. But before that bus could take Pema any closer to India, he and many others were arrested.

Tibetan sympathizers soon came and helped Pema and others get released—finally Pema would go to India. There, Pema’s older brother was a monk at the Sera Jey monastery in southern India, one of the largest monasteries in the world. According to Pema, the city surrounding this famous monastery holds about 10,000–15,000 Tibetan refugees. At Sera Jey, Pema lived alongside his brother as a monk—amongst a sea of at least 5,000 monks—studying Buddhist philosophy for 11 years. He said he preferred work over going to class, praying and keeping a schedule, and claimed he was a terrible student who often failed coursework. He had his eyes on something else.

“Monk life is the best life … happy … but I wanted to come to America,” Pema said. “I told my brother I wanted to go to America in 1999 and he was so mad.”

The main reason Pema wanted to come to America was so he could make money to send back to his family in Tibet to fulfill their dream, to meet the Dalai Lama. And on August 11, 2003, after four years of convincing his brother he should leave and trying his best to get a passport, which cost his brother $10,000, Pema found himself in New York City. He landed a job at a Chinese restaurant. He started as a dishwasher and quickly moved his way up to cook—a skill he had learned with the monks back at the monastery—a position he held there for two years.

“I just know only ‘thank you’ when I moved to New York City,” he said, laughing at himself and shaking his head, it seemed so ridiculous.

He didn’t have to pay rent and saved every penny he could during those two years to pay back his brother and send money to his parents to travel to India to meet the Dalai Lama, which they did (and he did as well earlier this year when the Dalai Lama was in Indianapolis).

For 10 years, Pema worked in restaurants, had a few odd jobs, and lived in Tennessee, Texas, North Carolina, Florida, Virginia and Massachusetts. During this time, he taught himself English and learned how much he loved the hibachi business because of the interactions with patrons.

“I’m a very good entertainer.” He passed us a charming glance and moved his arms around as if he was over a hibachi grill.

And in 2013, Pema fulfilled two of his own dreams: to be his own boss and to own a restaurant. At the time, one of his uncles, a 23-year owner of Anyetsang’s Restaurant in Bloomington, was looking to retire. With years of restaurant experience, Pema was the natural choice to take over so he left New York City for Indiana.

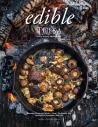

In Bloomington, there’s no doubt things are a lot different than they are in Tibet, India or even New York, but I suspect Pema’s attitude hasn’t changed much. His peaceful demeanor and happy-go-lucky attitude fill the cozy restaurant with warmth and welcoming. As soon as you walk in, you’re greeted with literature about the nearby Tibetan Mongolian Buddhist Cultural Center, the Dalai Lama and Tibet. And then there’s the food. The menu has traditional Tibetan dishes—like dumplings and khan amdo thugpa (noodle soup)—and Indian food because of all of the time Pema spent there, and a smattering of Thai dishes that are carryover from his uncle’s days as owner.

And after owning Anyetsang’s for a year, last year Pema traveled back to Tibet to see the family he hadn’t seen in 22 years. It took much effort and finagling for him to get there, but his mom was in the hospital so he was approved to visit. He has five sisters and two brothers who still live there, and countless nieces and nephews, and he saw them all. He sent me a photograph he took with his phone of his hometown last year when he was there. It’s like something out of National Geographic, nestled in between mountains lined with green trees and only a winding, gravel road connecting it and the 25 families who live there to the universe.

And then we moved from the inside dining area to the porch. We ate together under Tibetan prayer flags lining the shady outdoor patio. He made us potato dumplings, yellow curry with tofu and sticky white rice and spicy chicken pad Thai He told us more stories within stories, about coming to America, his family, traveling, what he sees for himself in the future and how much he’d like to go back to India, the place he called home for 11 years and hasn’t seen since.

And when I asked him if he’d stay in Bloomington he just smiled, leaned back in his casual way I’d already learned to admire and said, “I think I not go anywhere … I’ll stay. Work hard, make some money, go on vacation.”

And as the gentle breeze blew over us and I inconspicuously watched Pema eat next to me, I wondered what he looked like as a little boy at the foothills of Mt. Everest, as a monk in India, as a Tibetan refugee setting foot on American soil for the first time. I wanted to hold his hand in mine to see if I could feel the hope, happiness and energy inside of him. And then I took a bite of yellow curry and realized that’s exactly what I was doing.

Anyetsang’s Little Tibet Restaurant | 415 E. 4th St., Bloomington | 812.331.0122 | Anyetsangs.com

The Tibetan Mongolian Buddhist Cultural Center | 3655 Snoddy Rd., Bloomington | 812.336.6807 | tmbcc.org