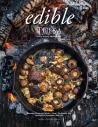

Go Wild in Your Pantry

recipes: Jason Michael Thomas

Jason Michael Thomas with his spicebush skewers.

Talking to a foraging chef passionate about the sweet wild pawpaw he has in the freezer, his stash of lightly roasted mulberry leaf tea that he picked and dried or tangy crimson sumac that he whizzed into a powder—it makes me want to get outdoors and fill my own pantry.

The thrill of reaping wild foods aside, for Chef Jason Michael Thomas foraging is also a significant part of his overall mission to be 100% local in produce and protein. In his kitchen, it’s local spicebush berries, not imported peppercorns, that add pepperiness to his food. And when he needs fresh acidity, he doesn’t turn to lemons. Lemons don’t grow in Indiana. But naturally tart sumac does, and it adds a similarly bright acidity. “Wood sorrel is another great source of acidity,” Jason says. “And so is lemon balm.”

Foraging is an ultimate food adventure. But it’s vital that you know what you’re doing. That is to protect not only yourself and anyone you’re feeding (don’t munch on a hunch), but nature as well. You don’t want to over-forage or deplete a spot, leaving nothing for next season to return.

For Jason, foraging is as normal an activity as grocery shopping is for others. Describing himself as a nerd, he explores the edibility of everything he finds. That includes using spicebush twigs as skewers, or drying nettle seeds that dropped to the bottom of his foraging bag late in the season. “Nettle seeds, you toast them and use like sesame seeds.”

We talk about a few of his favorite wild finds. Mulberry trees, too often seen as a pavement-discoloring nuisance, should be on everybody’s list to shake and gather the fruit. Mulberries produce a deep, dark juice that is full of beneficial nutrients. But did you know mulberry tree leaves are not to be overlooked? “I roast mulberry tree leaves briefly, at a low temperature, to deepen the flavor. Mulberry tea is like matcha,” Jason says. Flavor aside, mulberry leaves are high in fiber, iron and calcium.

From top, left to right: Fresh spicebush berries, wild garlic seeds, dried spicebush berries, dried sumac seeds, ground sumac seeds, goldenrod, dried goldenrod

Pawpaw, the largest fruit indigenous to the Midwest, is perhaps Jason’s favorite fruit to forage. “It’s magnificent to find a tropical fruit in the Midwest, where winters are so harsh.” He describes pawpaw, also known as the Indiana banana, as “somewhere between a banana, a cherimoya, a mango and a custard apple, sometimes with undertones of guava.” Much like bananas, some people love them green while others claim you should not touch them until they are brown. For Jason? “I prefer them green, when their skin just starts to give under pressure, like an avocado.”

Spicebush (Lindera benzoin) is a common native bush in Indiana, and in the same family as laurel. It is very giving, as its branches as well as the leaves and berries yield something to use in the kitchen, either as utensil or spice. The berries, once dried, are perfect to use as ground pepper. Like laurel, spicebush leaves add aroma, both fresh and dried. Dried spicebush leaves also make a mean tea. As for the spicebush branches, select the right ones to use as skewers: “Too thick and they tear the ingredients; too thin and they break,” he says.

His own urban farm, Urban Awareness Gardens, is an organic, sustainable, homegrown food lovers’ paradise. Lucky guests sit down for a private dinner that showcases what grows in his gardens as well as in nearby forests and meadows. On any given day the farm will be a hive of activities, from harvesting from the garden to drying, fermenting and preserving foraged wild foods. He makes jams, spice blends, leaf teas, finishing salts and all manner of pickles and preserves that he sells at farmers markets around town and on site.

There’s a sense of achievement in having a pantry stocked with preserves and condiments made from wild foods that you gathered yourself. Bring out your drying racks, clean the jars, make space in the kitchen and let the fun begin. Find out more or book a farm dinner at JasonMichaelThomas.MyShopify.com. Urban Awareness Gardens, 1637 Central Ave., Indianapolis.

PRESERVE THE BOUNTY

You don’t need a lot to preserve your foraged bounty for later. In fact, all you need is air, salt, water and time.

AIR

Air drying is a perfect way to preserve leaves, mushrooms and berries galore (including spicebush berries and sumac).

Leave your harvest in a single layer on drying racks until leaves crumble to the touch, and mushrooms and berries look all shriveled and dry. (You can also use a dehydrator or dry on baking sheets in a lowtemperature oven, see Dried Flower Power). Store dried foods in clean jars or other airtight containers, whole or ground into a powder. Build a spice cabinet with your own foraged ground sumac, spicebush berries and wild seeds galore. The dried leaves from stinging nettle, goldenrod (flowers and leaves), mulberry and other plants make delicious herbal teas.

Try your hand at making your own blends—that goes for teas as well as spice blends. Or start a collection of finishing salts, a mix of sea salt and a ground spice to use in a little sprinkle, right before serving a dish.

SALT & WATER

Lacto-fermentation is a preservation method that uses salt and water. A great example is sauerkraut, being simply shredded cabbage fermented in salt and water. Lacto-fermentation is a go-to for Chef Jason Michael Thomas when it comes to preserving the widest variety of fruits, vegetables, seeds and other things. He shares his lacto-fermenting process:

TIPS:

Use non-iodized salt.

Use spring water. Or filtered. Don’t use tap, because chlorine can affect the process.

The contents (vegetables, fruits, seeds) must be completely submerged to keep them from spoiling. Stick to a salt ratio of 2.5 percent of the combined weight of vegetables and water needed to submerge them.

STEPS:

Take a sanitized glass jar and weigh it. Add your vegetables, seeds or bulbs to the jar. Fill the jar the rest of the way with water ensuring, everything is covered, and weigh it again.

Do the math: Subtract the weight of the empty jar from the total weight of the filled jar to calculate the net weight. Add 2.5 percent of the net weight in salt (for instance, if the net weight is 1,000 grams you need to add 25 grams (5 teaspoons) of salt). To dissolve: Take some water from the jar and add the salt, then add it all back to the jar.

Place a weight (glass, ceramic, smooth stones or even a zip-top bag filled with water that fits in your vessel) and push it down on top of the contents to weigh them down.

Leave it in a cool place and check it every one or two days, removing any scum you see on the top of the water. In five days, you will notice some pleasant tartness and flavor development, but you might prefer to wait two weeks. Put it in the refrigerator after two weeks. It is now ready to eat, but if you prefer a tarter, stronger fermentation, you can leave it for up to four weeks.

DRIED FLOWER POWER

When blooms in your garden reach their peak, don’t let them wither. Pick them before they fall to the ground and take the floral bounty into the kitchen to dry. It’s what Jennifer Rubenstein, publisher of Edible Indy, begins late summer and early fall. She collects the seeds to dry for next year’s planting. And she dries flower petals in her oven to create her own flavored salts and teas. Here are some of her tips and tricks.

ROSE AND HIBISCUS

Preheat oven to 250°F (or use a dehydrator, if you have one).

Rose: Separate the petals and spread them in a single layer evenly on a baking sheet.

Hibiscus: Remove the stamen or pistil in the middle of the flower, leaving 4 petals to separate. Spread them in a single layer evenly on a baking sheet.

Dry rose petals in the oven for about 2–3 hours; hibiscus will take about 3–4 hours.

Both will turn brownish and flake when they are ready. To make rose or hibiscus salt: Grind the dried petals (rose or hibiscus) into a powder. Add sea salt (such as Maldon salt flakes) and maintain a 1:4 ratio of powder to salt. Mix and store in a jar. Use it as a finishing touch on any fish, chicken or vegetable dish.

To make tea: Flake rather than grind the petals, keeping bigger flakes. Mix rose and hibiscus or keep each as a separate tea. Simply steep in hot water to make a delicious floral tea.

Herbal teas like hibiscus and rose are naturally caff eine-free, contain antioxidants and help boost overall metabolism.

WILDFLOWER SEEDS

Right before wildflowers start to fall off , head out with brown paper sacks and fill them with wildflower heads. As they get drier and drier, all you need to do is simply fan or comb your fingers through the flowers and the seeds gathered inside the flowers fall out.

SUNFLOWER SEEDS

Collect sunflower heads before they are dried. Spread the heads on baking sheets and place them in a sunny place until they are dried (several weeks). Once dried, brush your fingers through the middle of the heads to release seeds to plant the following spring.

Store seeds in little paper bags and label them with what seeds they contain. Come next spring, all you need to do is sprinkle them in your garden and wait for fresh new flowers to emerge.

- Editor’s Note: All pottery and photography styling is by Gravesco Pottery. GravesCoPottery.com