Sustainability for the Real World

Sustainability. It’s one of the most talked about topics across all industries and a hot-button issue for politicians, educators, environmentalists and just about any and everyone with a pulse. But, what is sustainable? As it turns out, the definition varies from group to group, and when it comes to agriculture, what’s considered a sustainable practice for one commodity—say soybean or corn production—can be vastly different than it is on a dairy farm or cattle ranch.

According to BeefResearch.org and the Beef Checkoff program [part of the 1985 Farm Bill], the beef industry defines sustainability as “meeting growing global demand for beef by balancing environmental responsibility, economic opportunity and social diligence throughout the supply chain.”

And here in Indiana, on a 125-acre farm about 90 minutes northwest of Indianapolis, Bio Town Ag is doing just that.

TECHNOLOGY AND THE ENVIRONMENT

Bio Town Ag, a livestock farm in Reynolds, runs off an operating model that they say is both environmentally sound and financially stable. A typical multigenerational Midwest farm on paper, they’ve been in business since 1980 and for nearly three decades have dedicated themselves to implementing the kinds of technological advances that they claim enhance the sustainability of their livestock operations, while also working to eliminate environmental impacts of past agricultural production processes.

But just how does that work? Bio Town Ag President Brian Furrer explains how they’re working to turn animal waste into energy and why sustainable farming is so important for our future.

Edible Indy: Was there a pivotal point when you started thinking it’s time to be (more) aware of the environment and what sustainable farming really means?

Brian Furrer: There was a point early in the farm’s life when we recognized certain products were being underutilized. Essentially, a lot of really great feed material was being sent to a landfill. Unfortunately, this waste or byproduct [such as distiller’s grain; the part of the kernel of corn left after ethanol is produced from corn and husklage; the shucks from seed corn plants when corn is harvested for seed] can have negative connotations when, in reality, its nutrients are great for cattle.

EI: Is it fair to say your goal is to have a zerofootprint operation?

BF: Our goal as a farm is to continually lower our footprint. We still have to purchase the byproducts, but we have become extremely intentional on what we are bringing on the farm and how we are feeding our animals. It’s our objective to pull as many organic products away from a landfill and recycle them into beneficial products.

EI: What differentiates you from others?

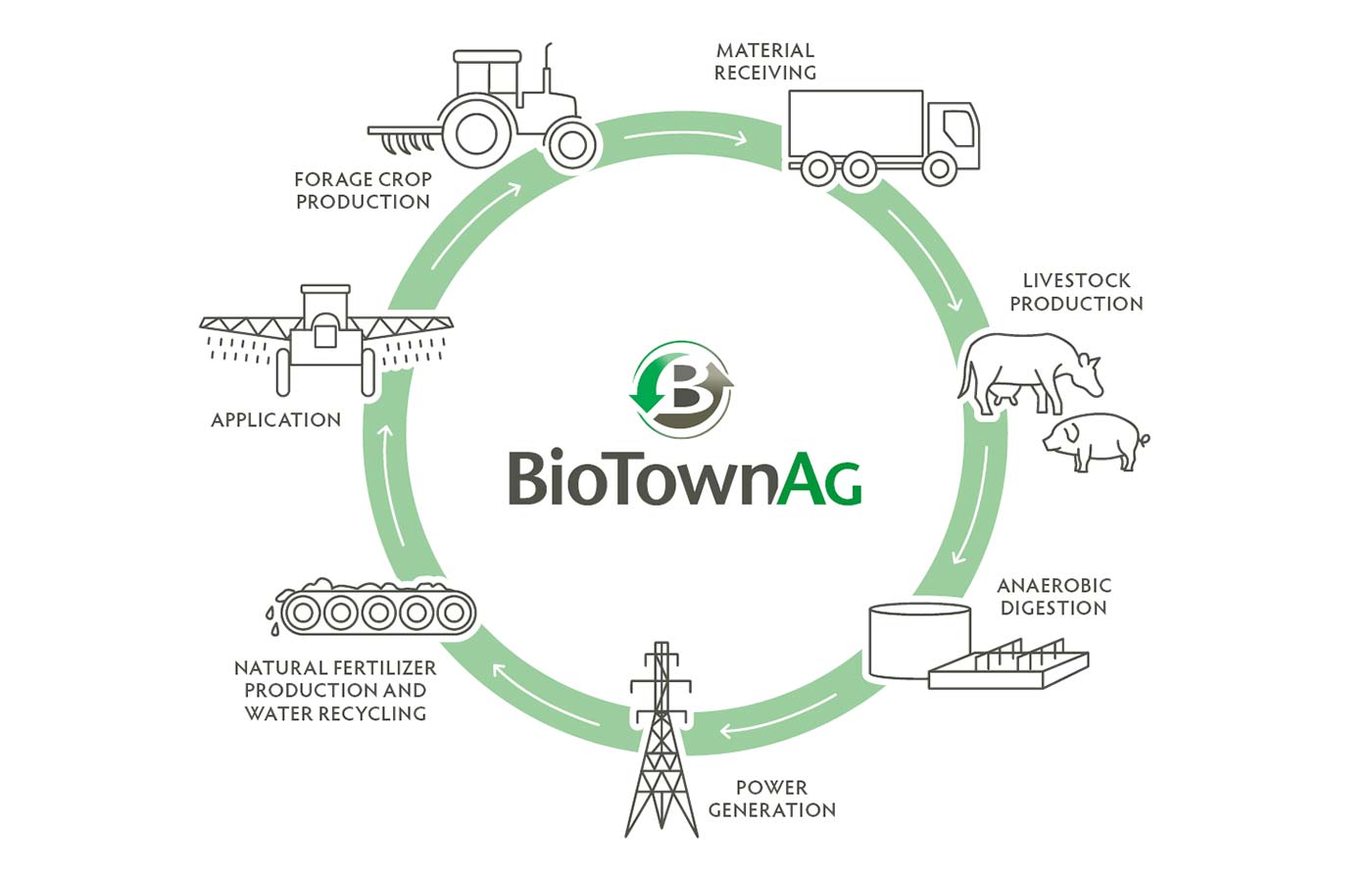

BF: Besides the vitamins and minerals that we give our cattle, everything we do is unique. Every day our cattle get the prescribed amount of substances and the rest of their intake is our very own byproduct mixture. We don’t grow anything for our cattle to eat, but actually find the products that other companies want to throw away and make better use of it. In our ecosystem, we bring in the byproduct, feed the byproduct to the cattle, take the cattle’s waste and extract energy from the waste that is used in our generators for energy.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency refers to municipal solid waste (MSW) as “various items consumers throw away after they are used,” such as “bottles and corrugated boxes, food, grass clippings, sofas, computers, tires and appliances,” but does not include “construction and demolition debris, municipal wastewater sludge, and other non-hazardous industrial wastes.”

EI: What are some of the biggest ways that define what you’re doing as sustainable?

BF: Bio Town Ag is the largest on-farm producer of electricity from waste in the world. We have methane digesters on site that take our cattle’s waste and create energy—something that no other farm is doing. Our farm puts twice as much energy on Northern Indiana Public Service Company power lines as Reynolds consumes. On the front and back end of what we do, we are feeding our cattle and taking waste processing to a whole new level.

EI: Is sustainability the key to the future of farming?

BF: When I was 10 years old, I started my first job on a farm cleaning pigs for 10 cents. Having been involved in agriculture for my entire life, I see plenty of opportunity. The problem with opportunities is that they come with a lot of hard work. When I walk through the grocery store, everything is so different than how agriculture was 40 years ago. We now have so many unique products including items that are categorized as organic and GMO, something that wasn’t necessarily prevalent back then. If you want to be a large-scale farmer, I can see individuals having a lot of trouble. But, if you want to be unique with what you’re investing your time in, I believe that you will find plenty of opportunity.

EI: How difficult is it to be a sustainable farming operation?

BF: Creating a sustainable farm can be difficult, but everything you do boils down to energy and commitment. As we look into the future of farming, I believe that being unsustainable will not be an option.

EI: Why aren’t more farms taking this approach?

BF: There are a lot of farms trying to take a sustainable approach, but everything takes time. For five years, I was constantly researching and studying every angle of sustainability before I broke ground on our initiatives. We’ve had people from all over the world visit our farm and while we are not perfect, I always know we’re doing something right when others want to imitate us.

Interested in visiting the farm? Find out how at BioTownAg.com, and learn more about this innovative Indiana farming operation. To help support the farm, keep a lookout for Bio Town Ag products, sold under the Legacy Maker brand, at Moody’s Butcher Shop and Market District.

MANAGING OUR TRASH

Worldwide, waste is a problem. But it’s not news. At least not here in the U.S. Nearly 30 years ago, January 23, 1980, in his State of the Union Address, President Carter urged Americans to take heed: “As individuals and as families, few of us can produce energy by ourselves,” he said. “But all of us can conserve energy—every one of us, every day of our lives. Tonight I call on you—in fact, all the people of America—to help our nation. Conserve energy. Eliminate waste.”

So we’ve known. Some might even say we were warned and failed to act—failed to heed the call to waste less and conserve more. But, while it’s true that we’ve been slow to take action, the good news is recycling is at an all-time high. The bad news, so is trash production.

With exception of recession years, municipal solid waste (MSW) rose from 88.1 million tons in 1960 to 262.4 million tons in 2015—increasing from 2.68 pounds per person per day to 4.48. [YIKES!!]

Each year, consumers throw away 16 billion diapers, 1.6 billion pens, 2 billion razor blades, 220 million car tires and enough aluminum to rebuild the U.S. commercial air fleet four times over.

The highest amount of MSW generation, 25.9%, is from paper and paperboard products—but it’s on a decline: in 2005 we threw away 84.8 million tons; in 2015, 68.1 million tons … which is great ...

But, conversely, MSW plastics generation grew from 8.2% in 1990 to 13.1% in 2015. In 1960, roughly 6% of MSW was recycled; in 1980, 16%; in 2000, 29%; in 2015, over 34%.

Similarly, in 1960 no MSW was combusted for energy production; in 2015, nearly 13% was. In 1960, 94% of MSW went to landfills; by 2015 it was less than 53%.

Today, nationwide, 35% of MSW is recycled, 13% combusted for energy production—an all-time high in the U.S.

Here in Indiana …

Per capita, the Hoosier State produces the sixth-highest amount of landfill waste.

Of the total, 16.7% is from plastics, the highest level in the country. Clearly, these numbers are shocking, but MSW only accounts for a small percentage of total waste. According to the World Bank’s “What a Waste” global database (2018), in developed countries nearly one third of generated waste is attributed to the building sector, with the construction industry being the “largest culprit, generating more than 90% of the total waste produced in a country.” Even so, you, we, us … as an individual, you can help.

What can you do …

- Invest in products that last longer and repair before you discard.

- Make a meal plan and shop for what you need, not what you don’t.

- Don’t buy single-use plastics.

- Cut back on junk mail subscriptions.

- When possible, buy in bulk and be cautious of excess packaging.

- Don’t use paper plates.

- Donate what can be reused or repurposed.

- Take your own reusable bags to the grocery.

- Learn how to compost.

- Recycle. Recycle. Recycle.

And don’t be afraid to call out your neighbor or friend who doesn’t recycle … it starts with you!

THE PROCESS: PUTTING ANIMAL WASTE TO GOOD USE

Recycling animal waste to make methane gas and using it to power three generators that produce 4.5 million watts of electricity per hour [enough power to run 45,000 light bulbs], isn’t easy. Nor is finding ways to repurpose byproduct into useful materials. But, at Bio Town Ag, they’ve narrowed down a process that does both those things and more.

Here’s how they make animal waste into good:

- Commodity beef and pork products yield food and fiber as they produce manure for the digester.

- In the digester, manure and other organic byproducts from industrial companies are “cooked” to produce methane gas and solid materials.

- The generators use the methane gas to produce electricity that goes on the grid.

- Liquid organic fertilizer from the digester gets applied to farm fields, replenishing the micronutrients that are not available in commercial NPK fertilizer.

- Water from the digester can provide irrigation for plants.

- Some of the solids from the digester become bedding for cattle.

- Other solids from the digester become potting soil for retail gardening outlets