Wondertree Farm: A Little Heaven on Earth

HAPPY BUT NOT

Is this heaven? The words came to me as I jumped out of my car onto the driveway of WonderTree Farm. Like Ray Liotta’s “Shoeless” Joe Jackson exiting the cornfields in Field of Dreams, I knew I’d arrived at something special on the edge of metropolitan Indianapolis. A cool breeze swept across the fields and with it the faint smell of farm animals. An eager Australian Shepherd ran my way, jumping up on my kneelength purple puffer coat and leaving muddy paw prints.

“Sorry about that,” said the tall man in the aviator sunglasses, baseball cap and Carhartt vest walking toward me from the farm truck. “He’s just a puppy.”

“No problem,” I said, with mask, notebook and phone in one hand, and the playful licks of the attention-hungry pup in the other.

“Hunter Smith,” the man responded, holding back a handshake he would’ve freely offered in the Before Times of COVID-19. “And this is Ranger.”

DIRTY

Smith, a retired Colts punter from 1999 to 2008, is the owner of WonderTree Farm, where he lives and works with his wife, Jen, and their four children: Josiah, 16; Samuel, 13; Lydia, 11; and Beau, 8. They bought the 24-acre homestead at auction back in 2015. As only the third or fourth owners since the land was originally deeded, the Smiths opted for a life on the farm after his retirement from the NFL and some soul searching about what’s next.

“I saw my kids happy but not dirty. They didn’t know how to work,” Smith recalls. “And just talking about it was one thing but giving them something to do was another.”

Smith and his wife began looking for a place on the Northside of Indianapolis where they could have space to grow a garden, raise some animals and give their children the kind of upbringing Smith had on his parents’ ranch in Texas.

“My dad was a true cowboy: fearless, strong, a maverick type. My mother is everything you’d expect from a Texas ranch wife: resilient, wise, a bit glamorous. Being raised by these two people in a working agricultural environment forged something in me I am forever grateful for,” Hunter says. “They showed me how to work. Through weather, injury, uncertainty and loss. They always worked. Hard. And they brought us kids along to work.”

But just as he said about his kids: Talking about owning a farm was one thing and doing it was another.

THE WINNING BID

The real estate market on the Northside of Indianapolis was hot at the time, and Smith was having trouble convincing any existing owners to sell to a former NFL player looking for a change. Eventually, a friend in Zionsville told him about an estate that would be coming to auction.

The land was expected to sell for millions, and Smith figured he would be outpriced immediately. But he and Jen had fallen in love with the land when they’d scouted it out earlier, so they showed up at the auction anyway. The auctioneer threw out $1 million as the opening bid, and no one budged. The bid was backed down by the hundreds of thousands and finally, at $100,000, someone raised their paddle. The bidding raced upward fairly quickly from there in $25,000 increments, and when there was another stall, Smith finally made his first and only bid. The price was already at the top number he and Jen had agreed on, and it was his one shot. There were four other bidders still in at that point.

Unexpectedly, the auctioneer paused, giving everyone a five-minute break to run numbers and presumably get back to bidding. But during the break, one of the other bidders approached Smith and asked what he was going to do with the place. When Smith told him he wanted to raise cows and kids, the man said, “Alright then, I’ll let you have it. My name is Wilburn Craft. I’ll be your neighbor.”

NO PLANS BUT NOSTALGIA

“The old people around here laugh at me a lot,” Smith says, as he explains his naïve approach at turning the abandoned property into a working farm. One of the first things they did was dam the ravine at the back of the property to make a pond. They cleared a lot of the brush by releasing a small herd of goats into the back pasture. And then there’s the big red barn.

“I had no plans other than nostalgia,” Smith tells me. “I wanted a barn like the one I grew up with in Texas.”

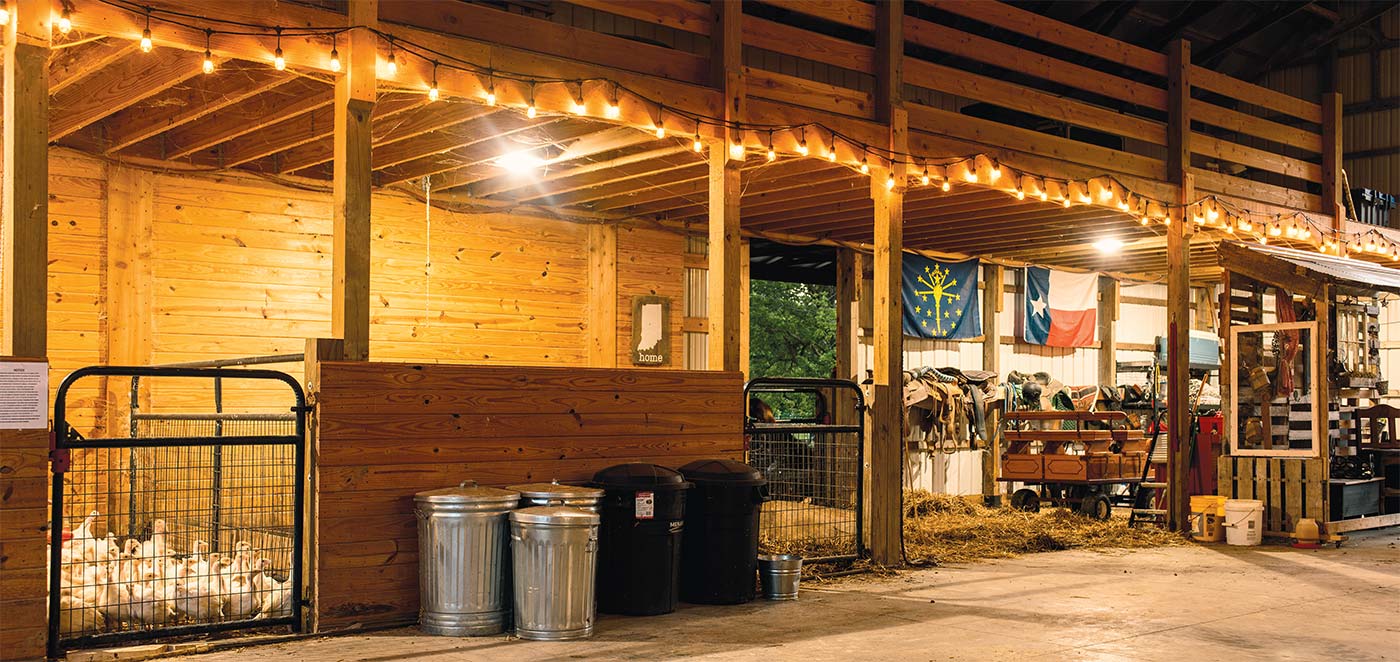

Smith designed and built the barn himself. The color red was important, so were the two wings on each side of the barn’s gambrel roofline and the large 16- by 16-foot doors. He ordered the supplies from an Amish company and then got to work with the help of a friend.

“This is where we start the process of the kids learning to work around the farm,” Smith recalls. “You teach your children to work by showing them how to do it.” Within a year, the shell of the WonderTree Farm barn was complete, even though its full use as the hub of their burgeoning meat, egg and dairy business wouldn’t be fully realized for a few more years.

Before we take a look inside, Smith tells me to wait until he opens the big doors—“It will help with the smell”—and turns on the lights.

The lights were a good idea, because there was so much to see inside the barn. From the lofts and paneling built from the wood of an old fence that Smith repurposed, to the large walk-in coolers and freezers that store the products WonderTree Farm sells during their drive-thru market during the winter and their market days during the summer. On the left, I found the source of the smell: a litter of Old Line Duroc feeder pigs. And from one corner of the barn to another, bouncing kittens, waddling ducks and a few strutting brood chickens.

“These are just for ambience. The working flock is out in the pasture,” Smith says, pointing to the poultry. Ranger bounds in and begins wrestling with the cats and playfully chasing the hens. I remember that Shoeless Joe line about heaven again, as I think about lions and lambs—or in this case puppies and chickens—lying down together.

IF YOU BUILD IT, THEY WILL COME

Chickens are, in fact, what got the Smiths into the “business” of farming beyond just a hobby farm. They started by buying 20 laying hens and 50 broiler chickens and ended up with enough eggs and meat to sell to a few friends and other members of the community. The next year, they saw an opportunity: Instead of just offering the products for sale, what if they brought people to the farm for an experience, too. So, they hosted a fall festival with more than 800 attendees. By the following year, they’d added a few head of cattle and hogs and began selling beef and pork, too.

“By the end of that second year, we had just enough beef and pork to make people think we had enough,” Smith recalls.

Now, as they prepare for their sixth year, they’ve acquired three additional farms, and they keep about 700 broilers, 350 laying hens, 90 head of cattle and 70 hogs at any given time, along with another 150 turkeys seasonally, plus the “ambience” chickens and ducks (which I dubbed “the talent”), five goats, three horses, two donkeys, six cats and four dogs. Their customers, 2,065 families within a seven-mile radius, are primarily their neighbors, a priority for Smith from the beginning.

“Because the family farm is gone, we want to be the family farm for our community,” Smith says. “Ultimately, we’d like to train other people to do this. I don’t know how we move forward as a society if don’t have something like this to be part of.”

DOING THINGS THE NEW OLD WAY

The Smiths aren’t just creating a modern version of the old family farm. Rather, they are attempting to use regenerative techniques to live lightly on the earth. Smith himself probably wouldn’t use that word; he tells me he’s not all that into the latest trends and terms. Instead, he explains how he’s doing things the old way: keeping old-line breeds of hogs and cattle, pasture raising all his animals, using his infrastructure and land for multiple purposes, even hiring local companies for humane meat processing that know how to prepare pastureraised meat for optimum taste and quality.

“We have a commitment to being antiquated—out of necessity—to farm healthy,” says Smith’s business partner, Chris Jackson, who began with WonderTree Farm in 2020. “That means less tech, less infrastructure, lighter on the land.”

That doesn’t mean Smith isn’t willing to innovate when necessary. For instance, Jackson brought with him the idea for “glamping” (a combination of “glamorous” and “camping,” though Jackson says it’s really just a term that means fully outfitted camping) at WonderTree Farm. They currently offer one “village” of four campsites where people can “come experience nature, culture and farm life.”

“It’s another way we can foster relationships between people, land and animals so they can understand where their food comes from,” Jackson says.

THE WONDER TREE

Before the tour ends, Smith tells me he has one more thing to show me.

“I hope it’s the Wonder Tree,” I say. And it is.

As we walk along a muddy path to the back of the original homestead, I’m relieved Smith had warned me to wear boots. We pass a stand of trees, and then over to the left I see the large white oak rising just at the top of the hill. Even though its limbs were bare—I visited in early March—the old giant inspires wonder all the same. One branch that hangs low and protrudes off to the south is as big as most of the other trees in the area.

“It’s 340 years old,” Smith says proudly. “At least that’s what the Internet told us,” he confesses. A Google search had given them a way to estimate the tree’s age by its circumference. “That means this tree was already 185 years old at the time of the Civil War.”

We both stood quietly for a minute just taking it in.

“We didn’t even know exactly what was back here when we first bought the place,” Smith says. A neighbor had told them about a 200-foot limb coming out of the side of an old tree, but there was so much undergrowth and so many other trees growing in an around it, that they weren’t able to assess its true size until the pasture was cleared.

“After we found it and figured out how old it is, the kids and I started to wonder: How many deer have run past this tree? Did Union soldiers camp out under it? How many farmers were tempted to cut it down? So we called it the Wonder Tree.”

Unfortunately, the old tree is dying. Smith expects they’ll have to cut it down later this year before it falls down.

“It’s sad, but it’s part of what we’re imparting to our kids: All things die,” Smith says.

They’ll turn the usable wood into something new for the farm, and they hope to leave a tall stump where they can build a deck to overlook the farm.

“We’ll make it a place people can come,” Smith explains. “We’ll honor the tree by making it its own place.”

The WonderTree name will carry on in other ways, too. Not only in the wonder of having such a beautiful piece of land for the community to visit and enjoy, but also the wonder, curiosity and willingness to try that have driven the Smiths from their first day here.

In fact, their whole story makes you kind of wonder: What would happen if a retired NFL player and his wife bought a farm and tried raising kids and cows and whole lot of chickens and hogs for a living? Well, it might just end up being like a little bit of heaven on earth.

Interested in checking out WonderTree Farm yourself?

There are several ways to join the Smiths for a family farm experience. Each Saturday from May through October (with soft openings and closings in April and November), join the Smiths on the farm to buy clean, locally raised pastured meats, farm-fresh eggs, raw dairy and local honey. You can also feed the animals, ride a horse, or play with the chickens while you’re here. The whole Smith family pulls together on Farm Days, so expect to see Josiah at the gate parking cars, Samuel helping with horse rides or with feed cups, Lydia making cotton candy, and Beau helping his brother fill feed cups. Jen offers horse rides on Sherman and Sunny, and Hunter pitches in wherever he’s needed.

The warmer months also mean glamping. WonderTree Farm currently has one “village” of four totally outfitted camp sites, including waterproof, bug-tight and breathable canvas bell tents stocked with everything from linens to lanterns. WonderTree can even pack a cooler of local meats to prepare on the fire or the grill that’s provided. Weekend campers also can “be a farmer” for a day with a full-farm tour on Saturdays.

During the winter months, WonderTree offers a drive-thru market, where customers literally drive through the big red barn to pick out and pay for meats, eggs and other products.

WonderTree Farm also has a membership program, WonderShare, which includes two customizable boxes of WonderTree meat, eggs and other products each month, free parking on Farm Days, special access to WonderTree events, discounts to the Glampground and other benefits.

- To learn more about WonderTree Farm, plan your Farm Day visit, register for glamping, or sign up for a WonderShare, check out WonderTreeFarm.com.